Abstract

This thesis investigates my relationship with the Rhône and Arve rivers in Geneva to understand what attracts me to their confluence. More broadly, it examines how we can connect, re-connect, and remain connected with nature within built environments, and how such connections might foster deeper appreciation. Through an expanded research question that considers sensory, conceptual, and media-based modes of engagement, I explore how nature is perceived, represented, and mediated. To contextualize these questions, I briefly make an incursion into the philosophy of technology to bring attention to how we view nature through inventions and interventions. The research combines case studies, interviews, and experiments through the lens of Environmental Aesthetics, with the goal of identifying new ways to appreciate nature and to help us sense vitality even in non-biological entities.

Introduction

“We have ourselves become

foreign to our everyday”

— Ronald W. Hepburn1

Since moving to Geneva in September 2024 for this master’s program at HEAD—Genève, I’ve walked over the viaduct in La Jonction over 400 times. This is the perfect spot to view the confluence of the Rhône and Arve rivers. Standing high above from a bird’s eye view and seeing this natural phenomenon for the first time, I was immediately in awe. My first encounter with the confluence was on a sunny afternoon, bringing out the teal of the Rhône and the white, milky qualities of the Arve. First photo taken on September 10, 2024 The waters of the rivers swirled before merging downstream.

First photo taken on September 10, 2024 The waters of the rivers swirled before merging downstream.

After walking over this bridge many times, I’ve witnessed the confluence in different conditions. On some days, there’s an imbalance of the rivers where one extends over the other, or a grey, cloudy sky dulls the colours. Looking back, I was lucky with my first impression of this sight. By walking this path repeatedly, I am able to appreciate my first experience because I have a frame of reference to compare it to. Walking was not only a means of getting from one place to another, but it also helped me connect with this place.[fig

In the context of art, walking has been explored as a medium of expression. Richard Long, a British land artist, creates artworks with nature. He performs with nature through the simple act of walking. His piece from 1967, A Line Made by Walking shows a visible straight line in the grass field of Wiltshire, England. The end result is a black and white photograph of the field with no animals or humans, just the landscape and a trace of the path. There’s a stark contrast between the wild and the line. Although there is no one visible in the photo, it serves as a reminder of a human presence. As time passes, we can imagine the line fading away and nature persisting.

As Spanish philosopher Marta Tafalla notes, “[Richard Long]’s relationship with nature is that of one who passes through it, who recovers old, little-used paths or who opens up new ones.”2 This points to our need to create our own paths, metaphorically and physically. Even in a built environment like a city, there are countless examples of paths designed by urban and landscape designers that are subverted by their walkers. We will look for the quickest and shortest path to our destination, often referred to as a “desire path”. You can see this right outside HEAD—Genève, where paths are created in the landscaped area around the main building. In contrast to Long’s meandering walks, these desire paths in an urban environment are a by-product of our need to efficiently arrive at our destination. We are trying to save time, but Long is taking his time.

I’m somewhat in the middle. I walk across the bridge as a means to arrive at my destination, but I am also there to enjoy the rivers intermingling and Mont Salève and the Jura Mountains in the distance. I try to strike a balance between getting there and taking it in. Walking along the Viaduc de la Jonction, I have no option but to go in a straight line, but this does not mean I cannot appreciate what surrounds me. Although I have to admit, as time goes on, my initial fascination with the confluence blunts. The honeymoon fades and as I start to live my life in Geneva, it becomes part of my everyday. Occasionally, my romance with the site is rekindled.

This is my starting point and the inspiration for my thesis—to explore this relationship I have with this location and understand why I’m drawn to it, despite having no prior connection to Geneva before my arrival. An underlying and more general concern is to examine how we can connect, re-connect, and stay connected with nature in our built environment, fostering a deeper appreciation for it. More specifically, how might sensory, conceptual, and mediated engagements with the natural world in urban environments foster aesthetic appreciation and lasting ecological relationships?

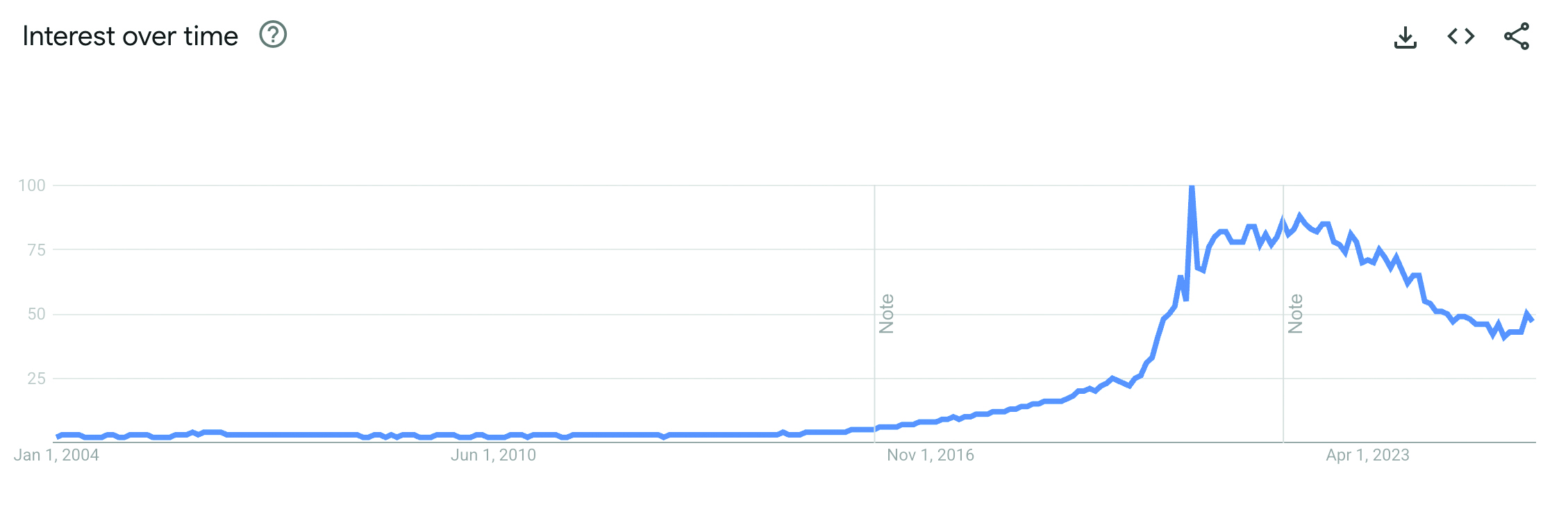

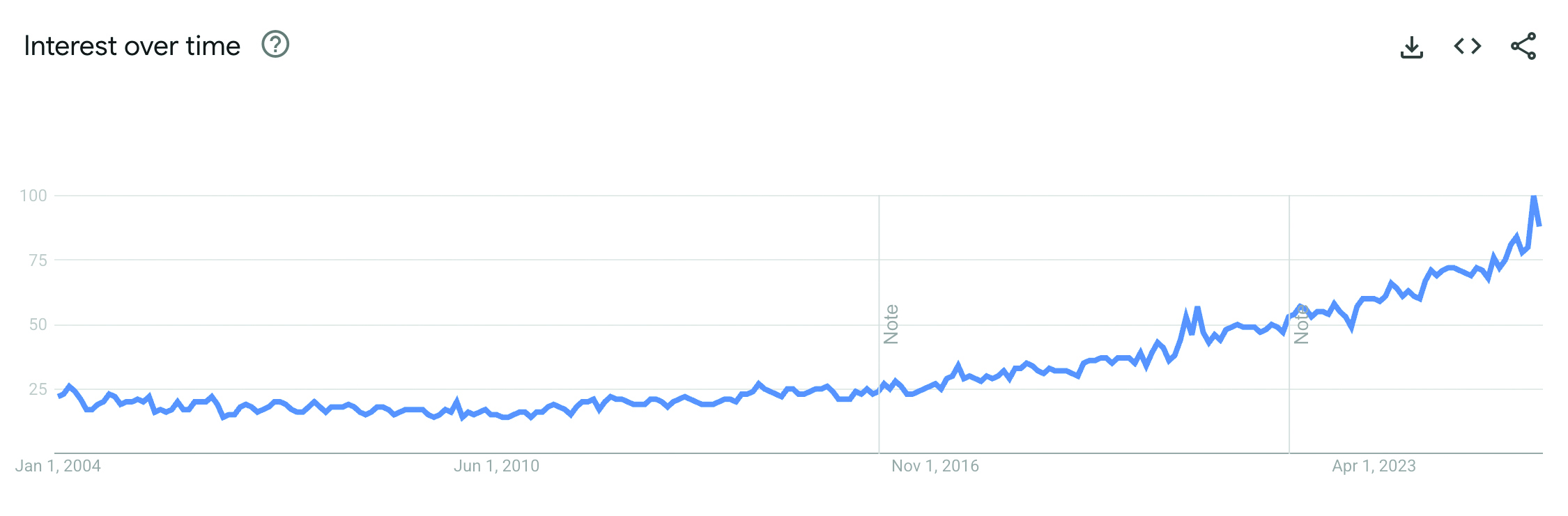

My methodology integrates two core dimensions: theoretical and practical. I will briefly make an incursion into the philosophy of technology to bring attention to how we view nature through inventions and intervention. However, the primary focus here will be on Environmental Aesthetics, a sub-branch of Aesthetics concerned with how we appreciate both natural and human-made environments. In this thesis, I will concentrate specifically on natural environments. Environmental Aesthetics first emerged in the 18th-century and re-emerged in the 1960s, driven partly by a shift away from viewing nature through the lens of art and toward recognizing it as an aesthetic experience in its own right. This renewed interest was also fueled by growing public concern for the environment and the need to make informed decisions about its preservation and use.3

Drawing from Environmental Aesthetics makes sense considering the context of this Master’s program, as design can afford aesthetic experiences. But more importantly, it aligns with the concept of mediating between nature and art. Environmental Aesthetics will provide a framework for analyzing my research and guiding my practical outcomes. Furthermore, by examining relevant case studies, I will de-centre my perspective and allow myself to take a broader view in approaching my main concern. I also interviewed sound artists to gain insight into how they perceive and engage with the natural world through sound, which will serve as a foundation for my diploma project.

I have produced a collection of photos which will serve as a basis to examine the visual aesthetic of the rivers, and I have been mapping the soundscape of La Jonction to understand the acoustic and sonic characteristics of the place.4 My goal is to understand how to appreciate nature through various sensing channels and media and to develop my practice of field documentation and recording.

I’ve narrowed down on a specific site for my field research. I purposefully want to work with a location that is close to home, literally. The confluence is just around the corner and is accessible to me at any time of day. Besides being a convenient location, this contributes to my goal of building a situated practice. I want to be able to interact wholeheartedly in the site of investigation to understand it, to embody it, to thoroughly grasp its variations and nuances. I have tried to approach my interviews in a similar spirit. In a world where everything is accessible by a mouse click, we can conduct interviews online with anyone around the world. However, spontaneity and magic are lost when we are not face-to-face, just as when we view nature only through the mediation of a screen.

My thesis unfolds in Chapter 2, inquiring into key concepts from aesthetics—such as beauty, the picturesque, and the critiques offered by pioneers of Environmental Aesthetics—to determine how we learn to appreciate nature beyond inherited visual conventions. Chapter 3 turns to photography, exploring how this everyday medium can continue to contribute to our perception and appreciation of the rivers. Chapter 4 then shifts toward more ‘scientistic’ modes of representation, examining data-driven approaches and the tensions between measurement and aesthetic value. This analysis leads into a discussion of mapping, from cartographic flatness to psychogeographic and sound mapping practices. Finally, in Chapter 5, the inquiry extends into sound, attentive listening, and the question of how diverse voices—human, technological, or natural—might allow the rivers to be revealed differently.

Before exploring the appreciation of nature through the lens of Environmental Aesthetics, I start with a few remarks about our relationship to technology and its connection to the natural world. I think it’s essential to set this context, especially because of technology’s ambivalence: while it can help us appreciate nature, it can also be detrimental to it.

Three Models for Technology-Nature Relation

A brief incursion into the philosophy of technology

There is a conventional contrast between technology and nature. One being a product of human invention and everything else that is not human. One that feels rigid and the other organic. One that is orderly and the other wild. However, this dichotomy, separation, and distance have contributed to the current problematic state of our relationship with our planet. But what if we thought about our relationship differently?

Mimesis

The ancient Greeks understood technology to be a form of mimesis, that is, “technology learns from or imitates nature”.5 This positions nature as a teacher, helping us find solutions to our human development. We can see instances of this with biomimicry and our desire to fly. From the first attempts of flapping our arms to studying the aerodynamic properties of birds.6 By learning from nature, we improved our flying techniques.

Air is not the only element we’ve conquered. We’ve built dams for various purposes such as irrigation, hydroelectricity, water supply, flood control and recreation. Dams date back to 4th century B.C.E. in Mesopotamia.7 They were constructed to supply water for crop irrigation, thereby sustaining a growing population. There’s no evidence of such dams based on animal inspiration. However, there is a recent development of looking to nature’s engineer, the beaver, to construct small dams. These small dams are aptly named “human-built beaver dam analogues” where they mimic beaver dams to use local materials and allow for permeability.8 Here, we are not only looking to nature for a solution to control the flow of water in a river, but also to rehabilitate the ecosystem.

Reserve

According to Martin Heidegger, traditional or pre-modern technology is poeisis (bringing something into presence). For example, the windmill draws on wind to produce energy. We are not controlling the element but instead using the wind as is to produce energy.9 On the other hand, modern technology forcefully attempts to reveal nature through extraction, and in this sense, nature is seen as a standing reserve. The world is subjected to the grip of technology and is reduced to a reserve of raw material. We are challenging what nature is capable of.

For example, we have altered the landscape of rivers and figured out that we can produce energy through hydroelectric power plants. There are 24 dams in total along the Rhône, with 19 located in France and 5 in Switzerland, which regulate the river’s flow while generating electricity. The Seujet dam located in Geneva’s city centre accounts for 1% of the city’s electricity consumption.10 In comparison to large hydrodams, this is a relatively small amount as it primarily serves as a way to regulate water flow. However, this small amount illustrates that technology will maximize a resource while revealing what it can do for us.

Prosthetic

The last model is based on the idea that technology is rooted in our human bodies. For Ernst Kapp, technology can be viewed as “organ projection”11 and in Marshal McLuhan’s words, “technology is an extension of man”.12 Where Kapp refers to bodily functions, McLuhan means the senses. These distinctions perhaps convey the same concept, because if we say “our eyes”, we are simultaneously referring to the organ and to our sight. For example, cameras, telescopes, and microscopes are all technologies that enhance our ability to see on different scales. Even though Kapp and McLuhan arrive at the same idea, I prefer Kapp’s concept of “organ projection” because it foregrounds a relationship to the body, connotes vitality, and connects technology operating as a system.

Without necessarily rejecting the first two models, I would like to propose that we attempt to rethink our relationship to nature through the prosthetic model. What if we saw nature through this lens, and instead of extraction, we are trying to view non-biological entities like a river as full of life with its own internal organs? The concept of viewing nature as alive with organs is not new. Ancient mythologies personified natural entities as deities and gods. The personification of nature is a clear example of human projection, as we shape non-biological entities into a human form.

The act of personification is an attempt to empathize with nature and to relate to the natural world around us through stories. In contrast, to view a natural entity through Kapp’s technological concept is to understand it and in a way that not only amplifies its function, but also potentially allows the entity to benefit from this understanding. This requires us to attempt to see nature as it is. However, I do wonder if this is even possible since we will view nature through our human perspectives and experiences. This idea of nature = nature is also one of the reasons that gave rise for the field of Environmental Aesthetics: how to appreciate nature separately from our appreciation of art and to view nature on its own terms. I am also hesitant about this separation, since the philosophy of art and Environmental Aesthetics belong in the same branch, and Environmental Aesthetics is often discussed in relation to art.

To conclude, attempts to control rivers have had detrimental environmental consequences. Instead, we should view rivers as a source of inspiration and design collaboratively with them. In the 1960s, the polluted Cheonggyecheon stream in Seoul was converted into an overpass highway. Thinking this would solve issues of people commuting into the city, it caused people to be displaced, increased air pollution and caused economic turmoil through the closure of businesses.13 It’s only recently that the river has been restored. The effects have been positive by allowing for floods to be managed in the urban environment while providing a public space for people to gather. Even if it’s human-made, it demonstrates that we should look to nature and to work with it before making drastic interventions.

The Picturesque View of La Jonction

An introduction to environmental aesthetics through paintings

That’s So Aesthetic!

The word “aesthetic” has been co-opted by people on social media to refer to something stylish or pretty, very often reducing what we see to the purely visual. Instead of saying, “that looks nice!”, we now proclaim, “that’s so aesthetic!”.[fig

Nature’s Beauty

In the 18th century during the Golden Age of Enlightenment Aesthetics, beauty was understood objectively through the concept of disinterestedness. This was a shift “from its classical associations with love, possession, and desire, emphasizing instead its disinterested character”.15 Philosophers such as David Hume, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Francis Hutcheson, while they didn’t all agree on all parts of aesthetic theory, they did “share the central idea of disinterested pleasure as independent from personal interest”.16 In other words, viewing an aesthetic object disinterestedly meant to view an object independently from one’s own interests, such as personal, religious or economic gains. For Immanuel Kant, disinterested pleasure also meant that an object’s genesis is irrelevant to the aesthetic judgement.17 To focus on the system in which an object is made is not attending to the object itself. For example, to aesthetically contemplate a flower is to examine its form instead of its biological processes and growth mechanisms. Essentially, Kant emphasized that aesthetic judgment requires attending solely to the object and its immediately perceived qualities. Therefore, to talk about our aesthetic judgments, we adopt an aesthetic attitude, appreciating its formal properties (colour, shapes, composition, texture, etc.) through disinterested contemplation.18

%20%20-%20(MeisterDrucke-138880).jpg)

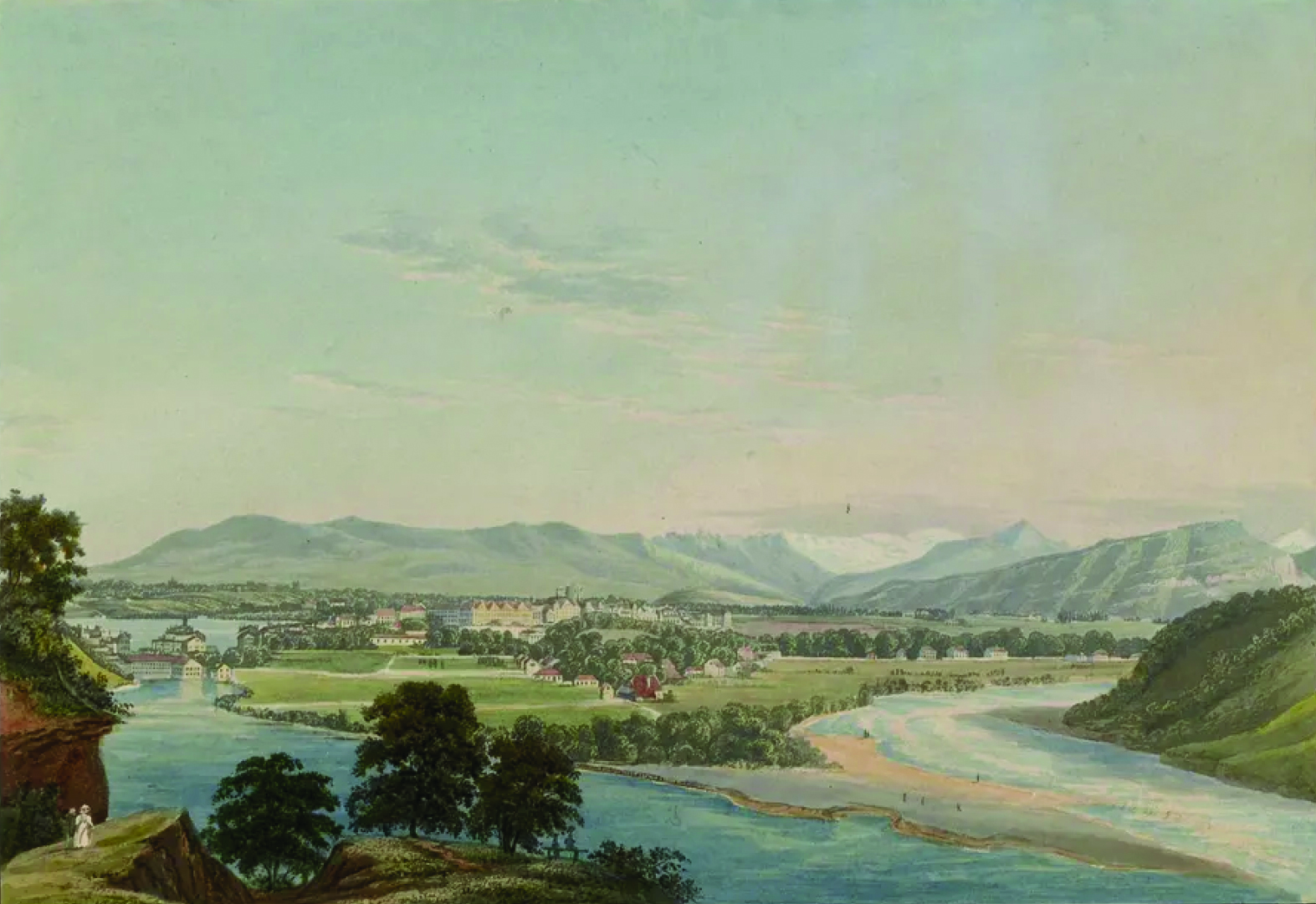

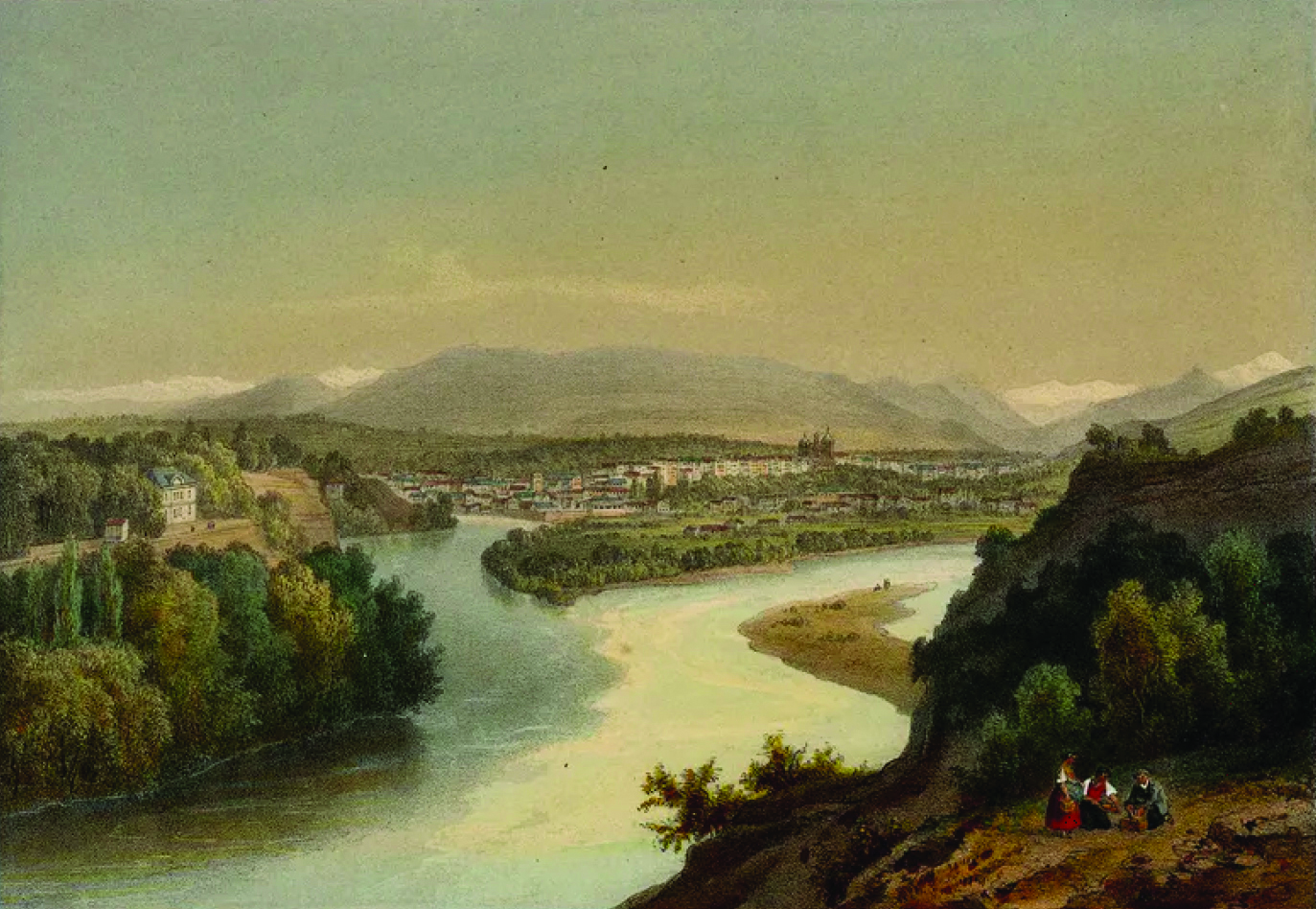

An analysis along the lines of an Enlightenment Aesthetics is to advert to the pictorial properties of a coloured engraving titled View of Geneva From The Confluence Of The Rhone And The Arve. For example, the composition utilizes the rule of two-thirds to balance the sky and ground. There’s a contrast between the vast sky and the detailed foreground. The soft colours and yellow undertones create a warm morning atmosphere. The inclusion of people in the painting also serves to establish a sense of scale. By now, we are familiar with formal descriptions and their legacy in art and design.

Perception of nature’s beauty also extends beyond mere description and is associated with the “picturesque”. Historically, this term acted as a label to simply communicate “the sort of landscape painted by artists” that had a balanced composition of a large outdoor view and is often a way to say “picture-like”.19 The concept of the picturesque influenced how we perceive nature, but it also motivated human behaviours. For example, beautiful views are often what we try to protect environmentally. This is also evident in scenic tourism, where the allure of natural beauty pushes travellers to destinations near and far.20 Historically, this is reflected in paintings featuring people in the foreground against natural backdrops, and today, in similarly situated selfies. Even if we regard nature’s beauty as objective and share broad agreement about what is beautiful, our appreciation often remains tied to self-interest, at least in terms of the hedonic dimension.

Landscape Model

Landscape paintings modelled our understanding of concepts like beauty and the picturesque, and contributed to the development of art criticism and theory. They also served as important aesthetic objects that fashioned our perspective on nature. Allen Carlson, a prominent figure in Environmental Aesthetics, noted that the way we appreciate nature is similar to how we appreciate landscape paintings:

When aesthetically appreciating landscape paintings … the emphasis is not on the actual object (the painting) nor on the object represented (the actual prospect); rather it is on the representation of the object and its represented features. Thus in landscape painting the appreciative emphasis is on those qualities which play an essential role in representing a prospect: visual qualities related to coloration and overall design.21

For example, in the landscape paintings of La Jonction[fig

The Landscape Model for the appreciation of nature brings up another key point mentioned by Ronald Hepburn: art is framed and nature is unframed.22 Paintings and other art forms are framed because they are bound by their dimensions, selection of scene, descriptions and curation around the artifact. In contrast, nature is unframed since it’s constantly changing from moment to moment, season to season, year to year. When we stand in a fixed point, we direct our attention which can be in multiple directions, and as we move through the environment, the horizon line of the landscape changes. In other words, art is contained, and nature is wild.

Given this brief historical context, we can now examine how to move beyond the picturesque and the frame, which can be particularly challenging within a visual culture that is increasingly shaped by screens in general and social media in particular. Hepburn and Carlson, along with many others in the field of environmental aesthetics, have answers to this question. I’ll apply their claims in discussing works produced by other artists, designers and myself with the goal of arriving at comprehensive models of appreciation.

A Photographic Study of the Rhône and Arve Rivers

Exploring the medium while also considering how it can deepen our appreciation of nature

Stack of printed photos | 2025

Over the three-month period from April to June 2025, I documented the Rhone and Arve rivers with a Nikon Z 6II with a 24–70mm f/4 S lens. The photos are of the rivers from various vantage points around the confluence, primarily from the viaduct. Initially, the photos served as image documentation and field research, but after printing and viewing them outside of a screen, I was drawn into a reflection on the medium of photography and how it can facilitate an appreciation of nature.

Stack of printed photos | 2025

Over the three-month period from April to June 2025, I documented the Rhone and Arve rivers with a Nikon Z 6II with a 24–70mm f/4 S lens. The photos are of the rivers from various vantage points around the confluence, primarily from the viaduct. Initially, the photos served as image documentation and field research, but after printing and viewing them outside of a screen, I was drawn into a reflection on the medium of photography and how it can facilitate an appreciation of nature.

Format and Display

Preparing stack of printed photos

A photograph immediately frames nature. This encompasses everything from hardware to post-production and how the photos are displayed within a space, as well as the most obvious, the photo frame. The photographic act is also rooted in framing. There are multiple steps that guide our decision before pressing the shutter button, known as “previsualization”. As Daniel Pinkas notes in “Santayana at the Harvard Camera Club”:

Preparing stack of printed photos

A photograph immediately frames nature. This encompasses everything from hardware to post-production and how the photos are displayed within a space, as well as the most obvious, the photo frame. The photographic act is also rooted in framing. There are multiple steps that guide our decision before pressing the shutter button, known as “previsualization”. As Daniel Pinkas notes in “Santayana at the Harvard Camera Club”:

[F]raming and shooting encapsulate the very essence of the photographic act, an act that culminates indeed in the “pressing of the button” but under the guidance of a conscious and sophisticated perceptive operation. The expressions “instant recognition of subject and form”, “spontaneity of judgment” and “composition by the eye”, are some of the ones used to designate what precedes and determines the decision to “press the button”.23

The photographic act can be described as the art of framing, a throughline that runs from the moment of composing an image to the way it is ultimately presented. Having a mental frame, however, does not only need to apply to taking a photo. As Stolnitz notes:

[T]he scene in nature lacks a frame and therefore cannot be grasped and comprehended by the eye and the mind…[A]lthough nature lacks a frame when it simply exists, apart from human perception, this is not true when it is apprehended aesthetically.24

The concept of the “frame” appears to be valuable not only in art but also in the aesthetic appreciation of nature. Without mentally framing nature in its presence, we might perceive it as wild and chaotic. This raises the question of how we might engage with the idea of framing and unframing in photography, and how such an approach could contribute to our aesthetic understanding of nature.

Photo display

Photo display

This exercise or arrangement attempts to address the frame issue. The photos printed are 12.6 cm x 9 cm on regular printer paper. The quality of the paper was less important since I was concerned with how to organize the photos in a coherent display. The focus was on how to present the final image once it is produced. Faced with multiple photos, the viewer can see beyond just one moment and perspective; more specifically, they can see a season in its entirety. This is reminiscent of David Hockney’s photographic collages, where he arranges photos from different vantage points and assembles them to create a new scene. In contrast, I’ve created an orderly display to represent the location of the confluence. There’s a clear horizontal axis with the viaduct, and a vertical axis with the dyke separating the rivers that leads to the lookout point.

The reproduction of the location is an attempt to address one of Carlson’s points about appropriately appreciating nature:

We must experience our background setting in all those ways in which we normally experience it, by sight, smell, touch, and whatever. However, we must experience it not as unobtrusive background, but as obtrusive foreground!25

Carlson argues we shouldn’t view nature simply as a backdrop. Instead, by actively engaging and directing our attention and letting nature disrupt us, we can then fully appreciate it. Of course a photo cannot replicate smell or touch. I’ll attempt to address what the medium of photography can achieve momentarily. The dimensions of the individual photos are small but the overall display could be huge if there were many photos. This would offer the viewer an approximation of being on the viaduct. There are close-ups to see details as if you were face-to-face with the rivers, which addresses Carlson’s point about the landscape model and the limitations of only viewing nature through colour and form.

One key aspect of nature is that we move through it. We are surrounded in it which brings us closer to nature and reduces the distance that is present in art.26 However, is it necessary to replicate nature as if you were there to appreciate it through photos?27

Collection of Evidence

Photos of the Arve River

Photos of the Arve River

According to Laura T. Di Summa in “Collecting What? Collecting as an Everyday Aesthetic Act”, “with the act of collecting, there is a sense of adventure and discovery.”28 In her paper, she refers to the collection of mundane objects, but this notion can also apply to our everyday environments—in my case, the confluence I pass by daily. I would often look forward to reaching the bottom of Bois de la Bâtie, catching the first glimpse of the rivers through the bridge archway. Before choosing this thesis topic, I took photos casually on my phone, mostly for myself and the occasional post on social media. I would look forward to the new formations of the confluence; even though my path was always the same, the adventure unfolded within the confluence itself. Once I committed to this research, my vision became more focused. I began carrying my digital camera, intentionally seeking various aspects of the confluence to photograph on my way to and from school.

This growing collection soon led me to reflect on the nature of digital photography itself. With digital photography, we are no longer constrained by the economic limits of film. This freedom allows us to document over a period of time and enables us to generate a series of photos at ease. Yet, with this abundance comes a new challenge: we can photograph anything, but we must ask whether we are truly capturing, collecting, curating or simply just amassing data. When digital photos are stored on our devices (mobile, computer or hard drives), they can easily become a “dark archive” where collections are forgotten or rarely accessed and enjoyed.29 This kind of “digital forgetting” mirrors the way we relate to nature in contemporary life: ever-present, yet too often overlooked.

It also becomes difficult to decide which photographs are “the best.” In this exercise, by presenting the images as a collection that viewers can pick up and rearrange, I invite them into the artistic process itself. As Thi Nguyen notes, “we often cherish the making of aesthetic judgements, for they require us to put our own efforts into it.”30 I intentionally give agency to the viewer, allowing them to organize the collection according to their own sensibility and invite them to work on their aesthetic judgement. In doing so, the work not only deepens their aesthetic engagement with the photos but also with the rivers. This also mirrors the constant change of the environment itself—each interaction changes the top photo of each stack, leaving them different for the next person.

A specific aesthetic experience occurs when we see a set of photos as a collection. We can view the object in multiple instances and appreciate it across different time periods and points of view. Through repetition, certain visual qualities are amplified, creating rhythm and intensity that a single image cannot achieve. When organized thoughtfully, this accumulation becomes a powerful visual form. With each new image, we are given a new element that contributes to our overall aesthetic judgement of the object. This is evident in Instagram carousel images, which allow users to post a series of related photos, as well as in monolithic coffee table photo books that highlight one object, or a museum curating a collection. This can be extended to a series of photos of the same subject matter in nature. It’s the diversity and variation that draw us in.

This diversity of photos, I would argue, acquaints us with the landscape. This implies that we appreciate learning about the environment, whether it’s the changes within a season or the appearance of the water’s surface at different times of day. As Hepburn puts it, “Nature is not a ‘given whole, ’ nor indeed is knowledge about it”.31 This suggests that nature cannot be aesthetically experienced as a whole but rather individually through its parts. Necessarily, through the appreciation and coordination of its parts, it also implies a “cognitivist” view that we appreciate nature through knowledge about it.32

Expressive Qualities

The preceding paragraphs may suggest that I believe in the transparency theory of photography. Photographic transparency is a recurring topic in writings on photography, and although the theory is questionable—since it claims that we are actually looking at the very object in the photo—it continues to shape how we discuss the medium.33 To briefly summarize the counterarguments to the transparency thesis: the bodily orientation argument claims that a photograph doesn’t allow us to spatially locate the depicted object or orient ourselves around it as we would in real space. The optical discontinuity argument, on the other hand, draws on scientific reasoning, pointing out that the light emitted from the photographed object is altered by the medium of display—whether on a screen or on paper—thus breaking the direct connection between the viewer and the object.34

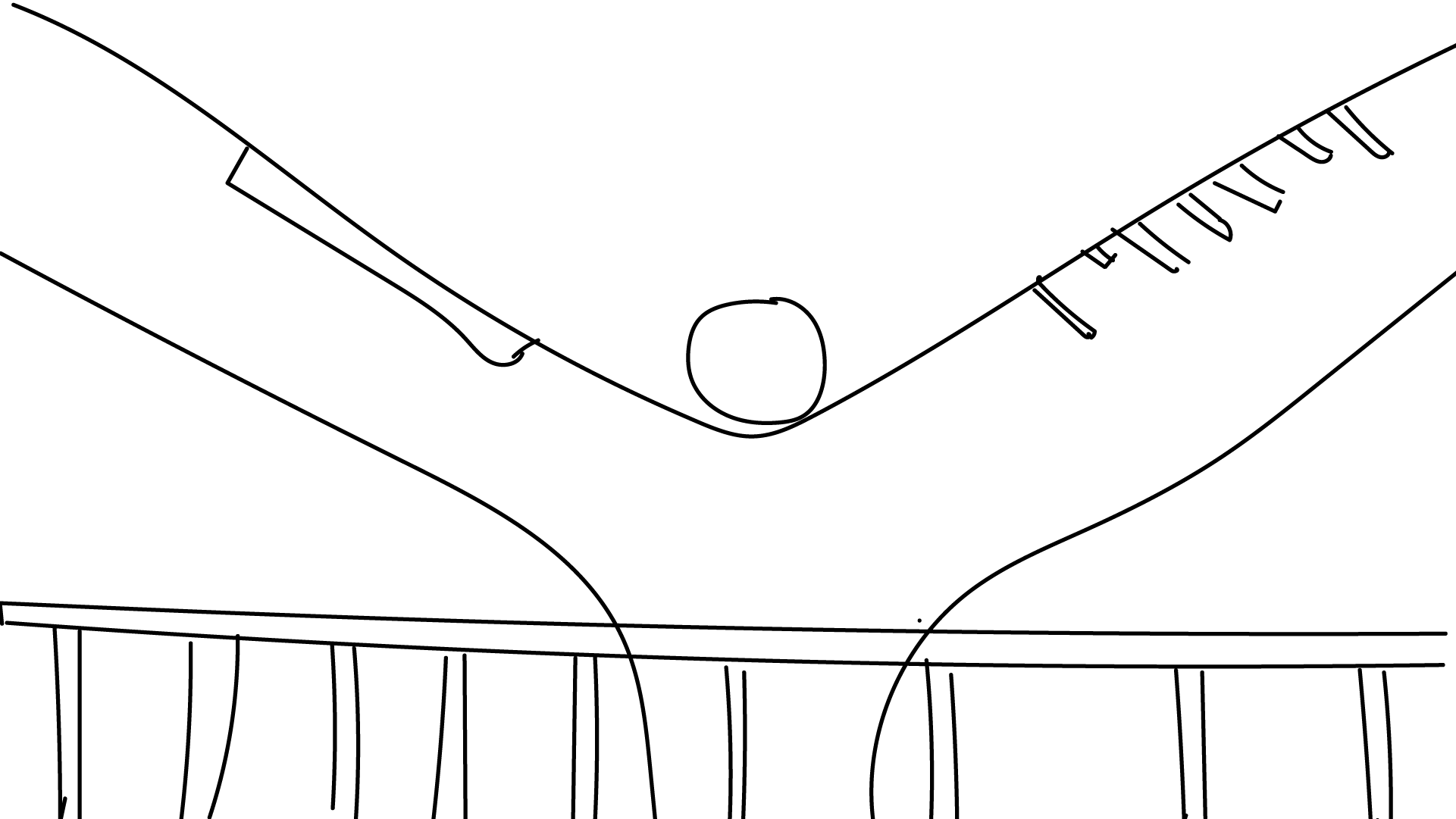

Long exposure photo of the confluence

Long exposure photo of the confluence

In “Looking at Nature through Photographs, Jonathan” Friday uses mirrors to support the transparency thesis. He states, “Mirror images have the same counterfactual dependence upon the appearance of the world that photographs do.”35 In other words, mirrors and photographs operate similarly: if you were to wave at yourself in a mirror, the reflected image would change accordingly, just as a camera would capture that change in a photograph. Friday continues:

Moreover, we treat mirror images as means by which we can see objects in the world that could not otherwise be seen given our position. For example, we can use mirrors to see what is behind us or around corners.36

Friday introduces mirrors to reinforce the transparency theory. He argues that they enable us to see things beyond our direct perspective. This idea opens an intriguing avenue for thinking about photography. Like mirrors, cameras can reveal what lies beyond our immediate position or attention. The notion of “blind spots” becomes a compelling concept, and I wonder what the camera renders visible that our eyes alone might miss?

One example is long exposure photography. This technique has the ability to capture motion and light over an extended period of time. In this photo, the aim is to document the aesthetic quality of confluence waves. While shimmering light offers a sense of movement in person, the naked eye cannot perceive the continuous, interwoven lines of water flowing in different directions. This distinctive and dynamic pattern is solely revealed and rendered by the photographic process.

Friday argues that the unique capability of photography lies in its power to isolate and capture nature’s expressiveness, offering viewers an aspect of that experience they cannot attain through direct, unmediated engagement.37 This goes beyond documentation and not presenting exactly what we see in person. We could say that this photo conveys a tranquil feeling due to the soft whisper-like waves and the calming blue-teal tones. But what exactly do we mean by “expressive”? According to Noël Carroll, this is how expression is understood generally and within the context of art:

At root, all expression theories maintain that something is art only if it expresses emotions. “Expression” comes from a Latin word which means “pressing outward”—as one squeezes the juice out of a grape. What expression theories claim is that art is essentially involved in bringing feelings to the surface, bringing them outward where they can be perceived by artists and audiences alike.38

Carroll goes into greater depth, but the key idea to take away is that something within the artist is transferred into the artwork, allowing audiences to perceive and extract that emotion—eliciting a corresponding feeling within themselves. However, since nature is not created by humans, how is it possible that we still experience emotional responses toward natural objects?

Whispers of the confluence

Whispers of the confluence

One might argue that the expressive qualities of a photograph stem from the depiction of a natural object, yet we also project our own feelings onto nature. For example, we call a tree a weeping willow. According to Hepburn, when we aesthetically contemplate nature, a rapprochement occurs between the viewer and the natural object—in other words, a sense of unity forms.39 This is what we mean when we say “to be one with nature.” For Hepburn, such unity emerges through a process of humanizing nature, attributing it human emotions.

Expressive contrast in a photograph also shapes our aesthetic experience. In design, we understand contrast as a key principle that helps us perceive and organize visual information. But what about in nature? For Hepburn, contrast in nature takes the form of a “paradoxical union” where opposing qualities coexist.40 His example is a boulder tumbling down a hill: a massive, seemingly immovable object suddenly in motion. Witnessing this contradiction produces an aesthetic experience that captivates us precisely because it defies our expectations of how such a natural object should behave.

In viewing long-exposure photographs, we might experience a similar paradox. The soft teal tones of the converging waves convey tranquillity, yet the visible motion of the water introduces a sense of vitality and excitement. This suggests that we appreciate multiple aspects of nature simultaneously—and that when these qualities are captured in a photograph, they evoke our aesthetic appreciation of both the photo and the natural world it depicts.

Fluvial Data

The tension between quantitative measures and the aesthetic qualities of landscapes

Scientistic Scenes

Attempts have long been made to translate what we find visually appealing into numbers. A simple example is the rule of thirds, where a composition is divided into nine equal parts by two horizontal and two vertical lines. By following these guides and positioning the subject at any intersection, the image becomes balanced through the contrast between the empty space and the focal point. Proportion, ratio, and symmetry have likewise been subjects of fascination since antiquity, notably in the Canon of Polykleitos, as an effort to define the ideal proportions of the human body.41 Beneath these systems lies a tension between perception and measurement, questioning whether the experience of beauty can ever be fully captured by numeracy.

The notion of disinterestedness invites us to view beauty objectively; therefore, the question of whether beauty itself can somehow be determined scientifically—from the perspective of a discipline grounded in objectivity—becomes one worth considering. A study conducted in 1969 by the Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture tried to determine which landscapes people preferred. They did so by showing participants sets of photos and had them rank seven landscape images. The researchers quantified the image by dividing the landscape into 8 weighted zones. A plastic grid is overlaid on the photo to outline various parts of the landscape.42 The top-ranked image featured a combination of a waterfall, stream, and lake. Perhaps the most obvious flaw in this study is the fact that participants are viewing photos rather than seeing the actual landscape. The authors of the paper are aware of this and state that, “research is needed to test how well preferences for photos of landscapes compare with preferences for those same landscapes when viewed on the ground.”43 In other words, to test and confirm the study’s results, the researchers would need to observe how the same participants rank landscapes when experiencing them in person. This would be an interesting follow-up study, though perhaps a considerable undertaking, not least because nature is in constant flux.

A plastic grid is overlaid on the photo to outline various parts of the landscape.42 The top-ranked image featured a combination of a waterfall, stream, and lake. Perhaps the most obvious flaw in this study is the fact that participants are viewing photos rather than seeing the actual landscape. The authors of the paper are aware of this and state that, “research is needed to test how well preferences for photos of landscapes compare with preferences for those same landscapes when viewed on the ground.”43 In other words, to test and confirm the study’s results, the researchers would need to observe how the same participants rank landscapes when experiencing them in person. This would be an interesting follow-up study, though perhaps a considerable undertaking, not least because nature is in constant flux.

With obvious ironic intentions, artists Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid conducted a similar study in the 1990s to determine what people wanted in a painting.44 They surveyed the american public, using the results of a poll to inform their painting choices. The findings revealed that the public preferred blue landscapes with water, people and animals. When the survey was conducted in other countries, it yielded remarkably similar results.

One might be skeptical of the project itself, but the point was never simply to paint what people want in a painting. One of the survey questions asked, “If you had unlimited resources and could commission your favorite artist to paint anything you wanted, what would it be?”45 The most common answer, perhaps unsurprisingly, was family portraits. Additionally, Holland Most Wanted Painting, Holland was the only country to prefer abstract paintings which also suggests that universal truths are unlikely when it comes to aesthetic preferences. This data, however, was ignored in favour of the project’s broader objective: to identify what the public desires collectively, rather than what individuals want personally.[fig

Most Wanted Painting, Holland was the only country to prefer abstract paintings which also suggests that universal truths are unlikely when it comes to aesthetic preferences. This data, however, was ignored in favour of the project’s broader objective: to identify what the public desires collectively, rather than what individuals want personally.[fig

There was still an element of interpretation in how Komar and Melamid chose to realize the final outcome. Although the end result took the form of a painting, it can also be understood as a kind of data visualization—a central theme of their project, which was based on a public poll. In their travelling exhibition The People’s Choice, they also displayed three-dimensional data visualizations alongside the paintings. These data visualizations had a significant impact on their assistant at the time. In an interview, Komar remarked:

[O]ur assistant, a young architect, said that in his view these graphs are the most aesthetic part of the show, that behind beauty and design of these abstract works, we see some truth, some actual fact of life.46

Here, instead of applying numbers to determine what is aesthetically pleasing, the numbers themselves have turned into an aesthetic object through visualizations. The paintings, data visualization and exhibition are all means to answer the question that Komar and Melamid set out, which is, what do people want in a painting? It appears that Komar and Melamid have found a (tongue and cheek) solution to their problem by employing a quasi-scientific methods. However, if taken literally, their approach would align with scientism, the idea that science can solve all problems. As described in Scientism: Prospects and Problems, scientism is

the view that only science can provide us with knowledge or rational belief, that only science can tell us what exists, and that only science can effectively address our moral and existential questions. As Alex Rosenberg says, scientism “is the conviction that the methods of science are the only reliable ways to secure knowledge of anything, ” the view that “science provides all the significant truths about reality”.47

While scientism suggests that science alone can yield a complete, objective understanding of the world—including our aesthetic experiences—this is not the position held within environmental aesthetics. Carlson’s Natural Environmental Model (NEM)48 is often associated with a cognitive approach, but he does not claim that scientific knowledge is the only valid way to appreciate nature. Rather, he argues that certain kinds of knowledge—drawn from natural history, ecology, geology, and related fields—can contribute to our aesthetic appreciation by helping us perceive natural environments more accurately and on their own terms. For Carlson, he makes a comparison to art-historical categories and how this could also be how we approach appreciating nature:

[A]s in art appreciation, in these cases, to appropriately appreciate the objects or landscapes in question aesthetically—to appreciate their grace, majesty, elegance, charm, cuteness, delicacy, or “disturbing weirdness”—it is necessary to perceive them in their correct categories. This requires knowing what they are and knowing something about them—in the cases in question, something of biology and geology. In general, it requires the knowledge given by the natural sciences.49

This comparison to art and using it as an analogy is criticized by Glenn Parsons:

[A] given natural thing will fall under a myriad of different categories, some more general and some more specific. In the case of art categories, it seems natural to employ the more specific categories, as when we view cubist portraits as a certain kind of work (cubist, say), rather than simply as paintings in some more generic sense. Presumably, we do this, in large part, because this is how their creators intended them to be viewed. But in the case of nature, the matter is less clear: can we view a Venus Fly-Trap merely as a plant, or ought we view it as a very specific kind of plant (carnivorous), with specific needs, traits and environment?50

The challenge here is that we can view art in a specific way due to context and the artist’s intentions. To expand on the cubist painting, we wouldn’t judge it from a contemporary lens because the painting was not created during this time (although, our knowledge about art now does influence how we talk about art in the past). With nature, there are many different disciplines to approach it as Parsons has pointed out, so then how do we choose which natural science to apply our aesthetic judgement?

One possible approach would be to draw on behavioural ecology, which examines the evolutionary foundations of animal behaviour in relation to environments of evolutionary adaptations (EEA).51 As Steven Pinker notes in How the Mind Works:

The biologist George Orians, an expert on the behavioral ecology of birds, recently turned his eye to the behavioral ecology of humans. With Judith Heerwagen, Stephen Kaplan, Rachel Kaplan, and others, he argues that our sense of natural beauty is the mechanism that drove our ancestors into suitable habitats. We innately find savannas

Tropical Savanna Taita Hills Wildlife Sanctuary, Kenya | Photo by Christopher T Cooper beautiful, but we also like a landscape that is easy to explore and remember, and that we have lived in long enough to know its ins and outs.52

To confirm this point, an experiment was conducted by George Orians with american children and adults who were shown various landscapes and asked to indicate how much they would like to visit or live in the depicted places. No one liked deserts and rainforest but everyone preferred savannas Tree Savanna Tarangire National Park, Tanzania | Photo by ProfessorX.53 The author points out that savannas allow us to survey the land at a glance for predators and for resources, while offering safety. There are important methodological limitations to Orians’ experiment. First, the study surveyed only an american population, making it difficult to support any claim of universal preference without cross-cultural comparison. Second, adults in the study also showed strong preferences for deciduous and coniferous forests—the very landscapes common across the United States. As Pinker notes, this suggests that people may simply feel at ease in environments that resemble familiar habitats. Rather than pointing to a “mystical longing for ancient homelands, ”54 these findings imply that our attraction to certain landscapes may arise not only from their aesthetic qualities but also from their perceived functionality.

Tree Savanna Tarangire National Park, Tanzania | Photo by ProfessorX.53 The author points out that savannas allow us to survey the land at a glance for predators and for resources, while offering safety. There are important methodological limitations to Orians’ experiment. First, the study surveyed only an american population, making it difficult to support any claim of universal preference without cross-cultural comparison. Second, adults in the study also showed strong preferences for deciduous and coniferous forests—the very landscapes common across the United States. As Pinker notes, this suggests that people may simply feel at ease in environments that resemble familiar habitats. Rather than pointing to a “mystical longing for ancient homelands, ”54 these findings imply that our attraction to certain landscapes may arise not only from their aesthetic qualities but also from their perceived functionality.

Pinker goes on to say: “The geographer Jay Appleton succinctly captured what makes a landscape appealing: prospect and refuge, or seeing without being seen.”55 Appleton is not making an evolutionary claim about ancestral environments, but rather highlighting the practical qualities that can make certain landscapes appealing to us. The point is not that we possess an innate longing for any specific habitat—otherwise we might all feel compelled to return to savannas (which, personally, I do not, nor had I ever considered until encountering this study). Instead, Appleton suggests that certain spatial conditions—vantage, openness, shelter—can structure how safe, oriented, or attentive we feel within a place.

When I consider my own attraction to the confluence from this practical perspective, the relevance becomes clearer. My habitual vantage point is high above on the viaduct, where I gain a bird’s-eye view of the rivers. The city lies in the near distance, the mountains beyond. Perhaps it is this openness—similar in some respects to a savanna—that draws me in. There is also something compelling about being elevated yet slightly concealed: people below cannot easily see me, while I can survey the landscape at a glance. This perspective affords both prospect and refuge, echoing the structure of a map in the way it provides an immediate overview of the terrain.

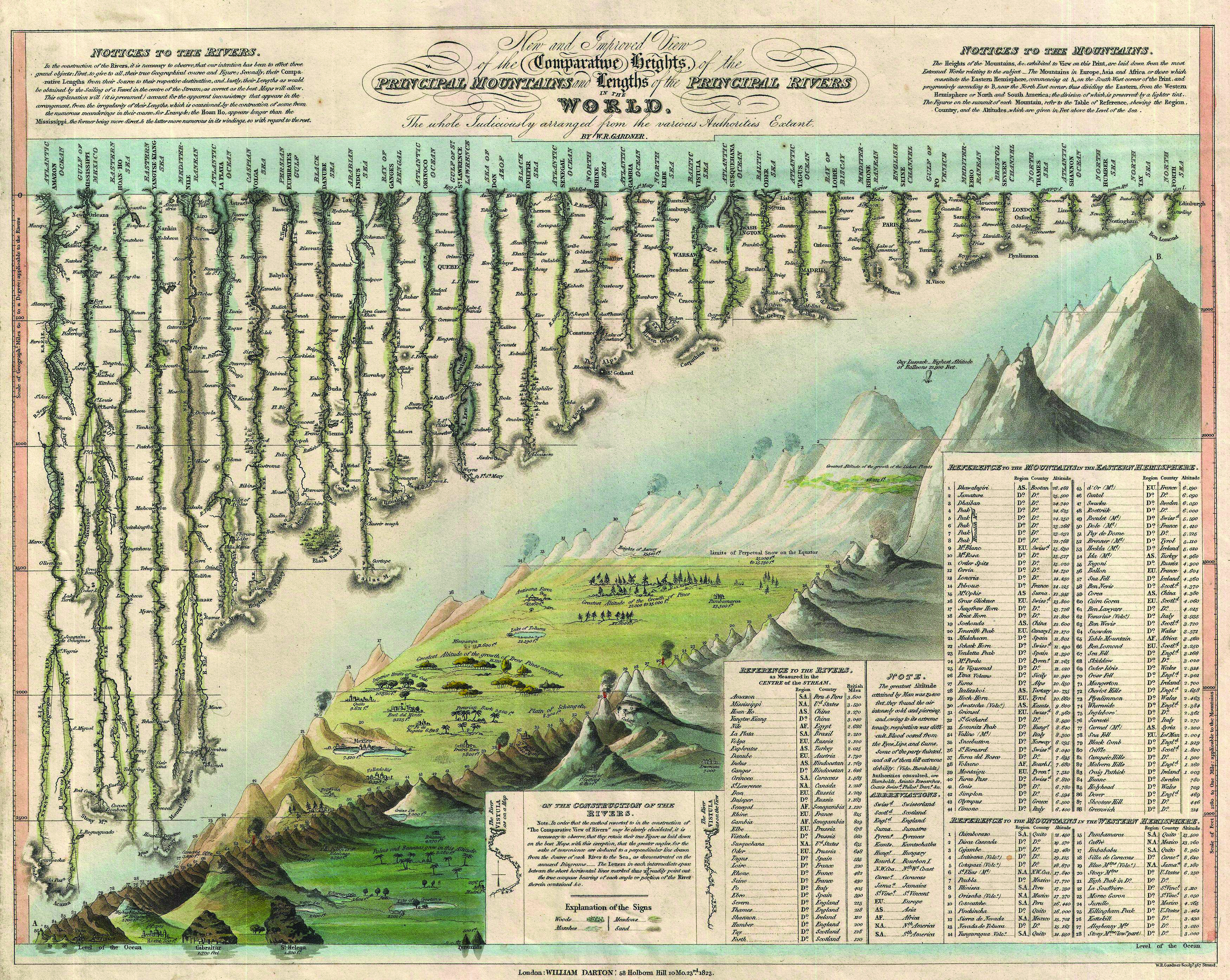

Mapping the Land

Mapping can help us make sense of the world around us, but at what cost? We take 3D space and collapse it into 2D through translation and distill only the relevant information for the viewer so that we can orient ourselves on the map, but also in the actual 3D space. Of course challenges arise from this dimensional reduction, and as Alan Henrikson aptly noted, “All maps lie flat; all maps lie”.56 One reason is that we are representing the world in a 2-dimensional space and, depending on the objective of the map, the cartographer chooses which aspect—shape, area, distance or direction (acronym: “sadd”)—to focus on.57 If one incorporates three fundamental components in a map, it’s inevitable, because of the complex nature of the world, that a fourth will be lost.58

Beyond the technical aspect and the challenges they pose, there are also biases from the cartographer. Ruben Pater states in The Politics of Design:

The notion that maps provide an objective or scientific depiction of the world is a common myth. The graphic nature of maps simplifies reality, giving makers and users a sense of power without social and ecological responsibilities.59

To add to Pater, the issue is not only a sense of power, but also, according to the critical framework developed by Peter A. Hall and Patricio Davila in Critical Visualizations: Rethinking the representation of data, it’s how “data assemblages enhance and maintain the exercise of power”.60 A classic example is the Mercator map projection, which emphasizes the Northern Hemisphere by excluding the poles and visually lowering the equator.61 This distorts our perception of the world by exaggerating the scale of landmasses in the upper hemisphere. The effect isn’t only due to size distortion, but also to our tendency to interpret elements placed at the top of an image as more important within a hierarchical structure. In doing so, the projection also reinforces historical power structures rooted in European colonialism.

The last issue I’ll address is the idea that the cartographer renders what is out of sight. Henrikson observed:

Unlike a photograph or a painting, a map represents its subject schematically. Because the areas it shows are too large to be seen in their entirety, and may include regions that have never been explored, some principle of extrapolation—from the known to the unknown—is needed.62

This means that when a cartographer creates a map, we might assume they have personally explored every area they depict. In practice, this is impossible—not only because of the sheer scale of the territory, but also because some regions may be inaccessible. As a result, the cartographer must rely on what is already known through exploration and then extend their knowledge, using the logic and conventions of the mapping system, to imagine how the unknown areas should appear.

Thus, maps can be problematic because they incorporate technical limitations, the cartographer’s biases, and the tendency to depict unknown areas as if they were fully known. In addition, they attempt to freeze landscapes that are constantly changing. Geography illustrates this instability through the coastline paradox: the edges of landmasses can never be precisely measured because coastlines, rivers, and other bodies of water continuously shift over time.63 Yet this did not prevent Darton and Gardner from producing their Comparative Chart of World Mountains and Rivers[fig

When it comes to maps, size inevitably plays a role because of the translation of scale, but what other qualities should we attend to, and how might they shape our aesthetic experience of maps and in extension, nature? In Envisioning Information, Edward Tufte introduces the notion of “flatland” to describe how the vibrancy and complexity of the living world become compressed into two-dimensional diagrams:

All communication between the readers of an image and the makers of an image must now take place on a two-dimensional surface. Escaping this flatland is the essential task of envisioning information—for all the interesting worlds (physical, biological, imaginary, human) that we seek to understand are inevitably and happily multivariate in nature. Not flatlands.64

Incidentally, Tufte’s interventions are relatively modest, grounded in a commitment to representing

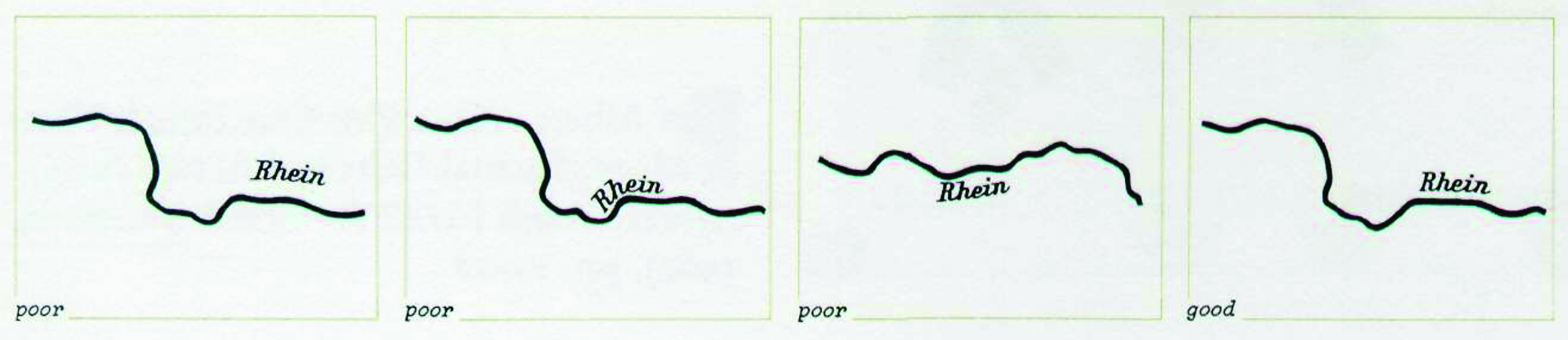

information as accurately and legibly as possible by offering practical strategies. For example, positioning labels[fig

Tufte considers the Tiber River to be a tranquil area, but the use of black linework against dark surroundings—undercuts this sense of calm Map of Rome by Giambattista Nolli 1748. Still, it may be a stretch to expect a map like this, even with adjusted shading

Map of Rome by Giambattista Nolli 1748. Still, it may be a stretch to expect a map like this, even with adjusted shading Tufte Redesign, to convey tranquility when its primary purpose is to represent the topography of Rome rather than evoke an atmosphere. Moreover, the dense shading of the river lines creates a subtle three-dimensional texture, more reminiscent of tree-bark illustration than of a serene waterscape.

Tufte Redesign, to convey tranquility when its primary purpose is to represent the topography of Rome rather than evoke an atmosphere. Moreover, the dense shading of the river lines creates a subtle three-dimensional texture, more reminiscent of tree-bark illustration than of a serene waterscape.

While Tufte’s interventions are modest, the concept of “flatland” and trying to escape it, is worth considering further. When Harold Fisk, a geologist and cartographer, was working for the US Army Corps of Engineers, this is what he had in mind: to explore the ever shifting nature of the lower Mississippi River through time and space.66 To do this, he separated the river’s movements into different time periods, each represented by a distinct colour[fig

Although the Mississippi River appears to have shifted course on its own, many of its changes were driven by European settlers, who reshaped the landscape by digging new channels, clearing logjams, and installing floodgate systems.68 These interventions point to a broader issue of land control and our separation from nature, especially when considering the context in which they were produced—namely, a government report on “the nature and origin of the Alluvial Valley of the Lower Mississippi River.”69 As Vanessa de Oliveira Andreotti notes, “The first thing that separability does is that it turns the land, in its broader sense, into property.”70 Her observation demonstrates how from a colonial perspective, nature has been treated as something to be owned, managed, and controlled.

In Imagine, authors François et al. quote Alfred Korzyski, “the map is not the territory” and proceed to pose a series of questions:

What landscapes await beyond our vision? What relationships remain uncharted? What ways of knowing lie just beyond our grasp?71

Psychogeography

To address these questions, we might turn to psychogeographic maps as a way to extend our relationship to the environment. As Merlin Coverley notes, “psychogeography, as the word suggests, describes the point at which psychology and geography collide, a means of calibrating the behavioural impact of place.”72 In essence, it considers how environments affect our mood and how we engage in a space. The concept has roots with the Situationist movement in France, where wandering and drifting without a destination becomes a method for re-orienting oneself within the urban landscape and cultivating personal connections to place.73

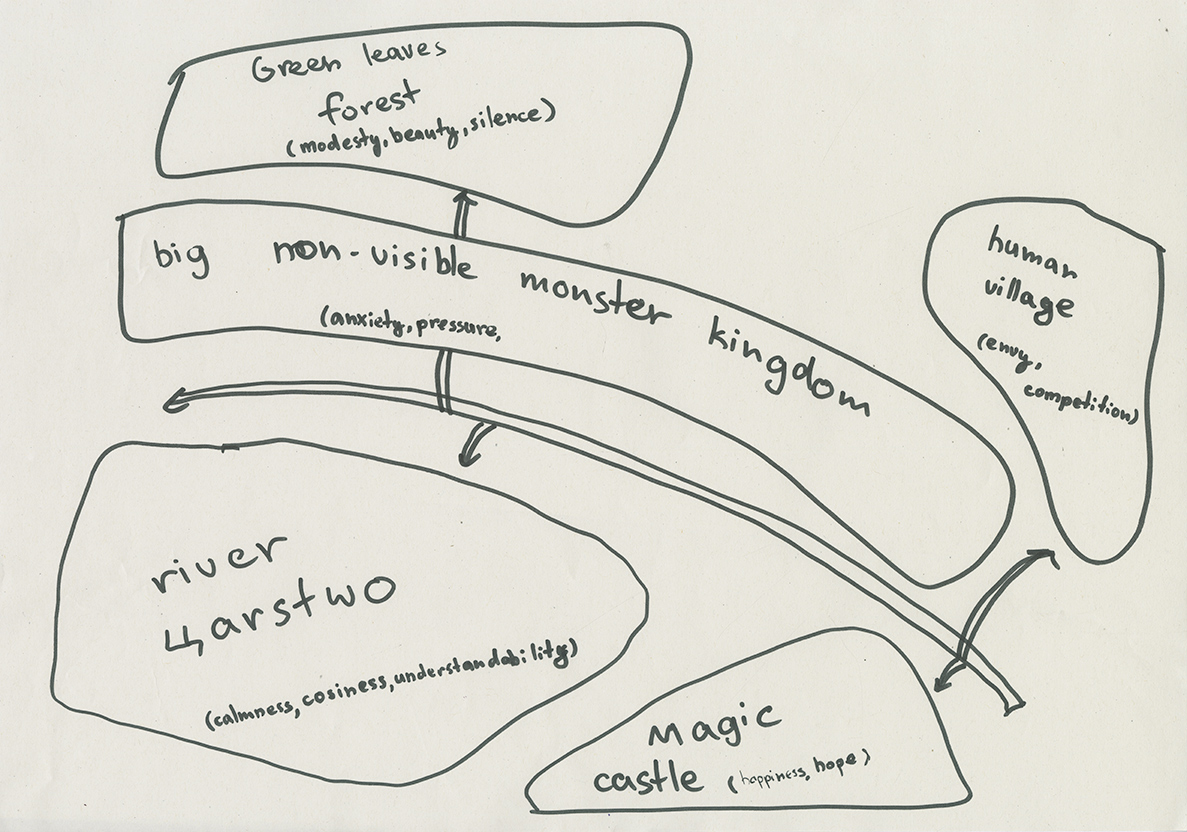

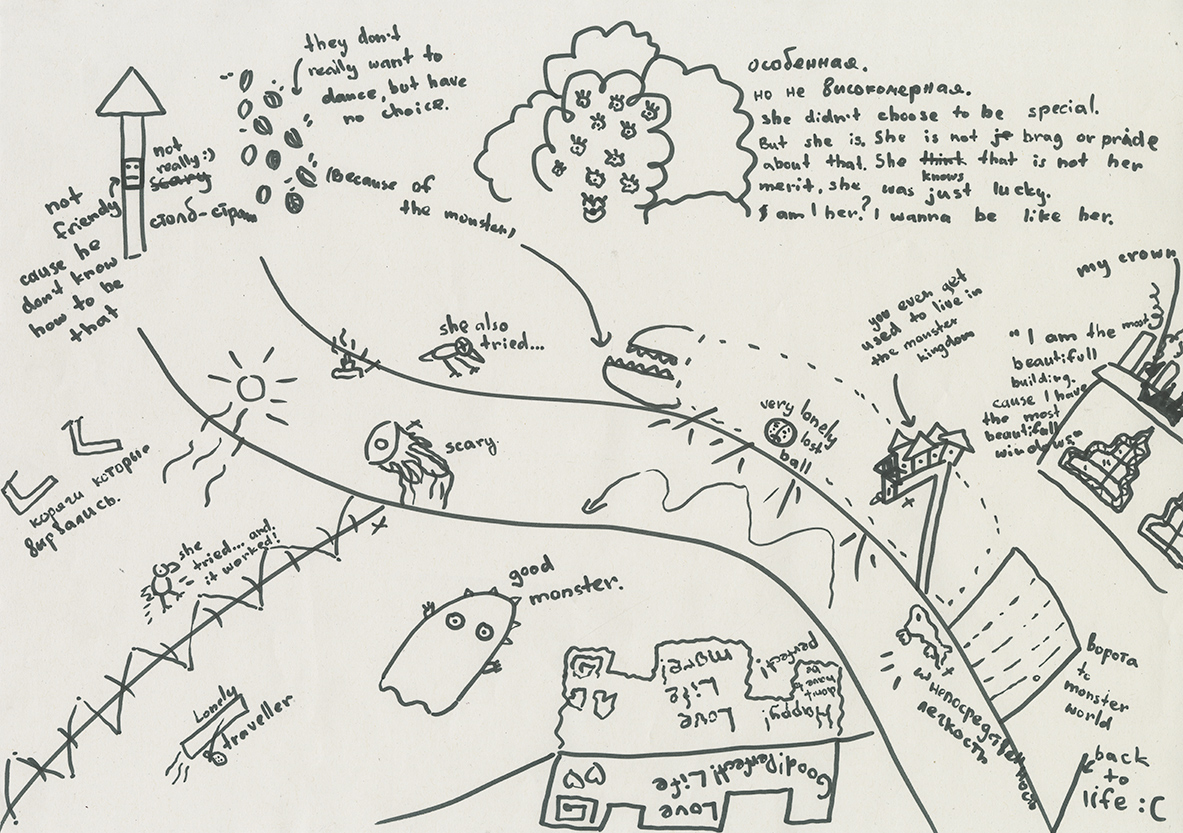

This approach inspired “Exercice #4: Arpentages” in Exercise d’Observation by Nicolas Nova, in which the readers are encouraged to observe an environment through drifting and attentive noticing. Nova suggests focusing on objects, people, smells or sounds and then creating a map based on those observations.74 A similar method informed an exercise given by Sabrina Calvo in our Media Design program during a virtual-reality workshop. Calvo’s goal was to have us deepen our awareness of the environment so that we could design virtual spaces with greater sensitivity.

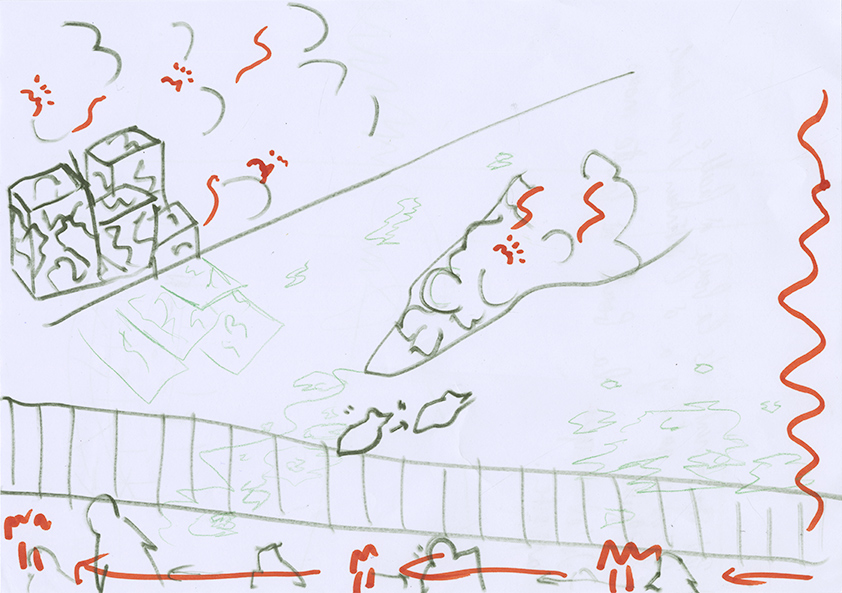

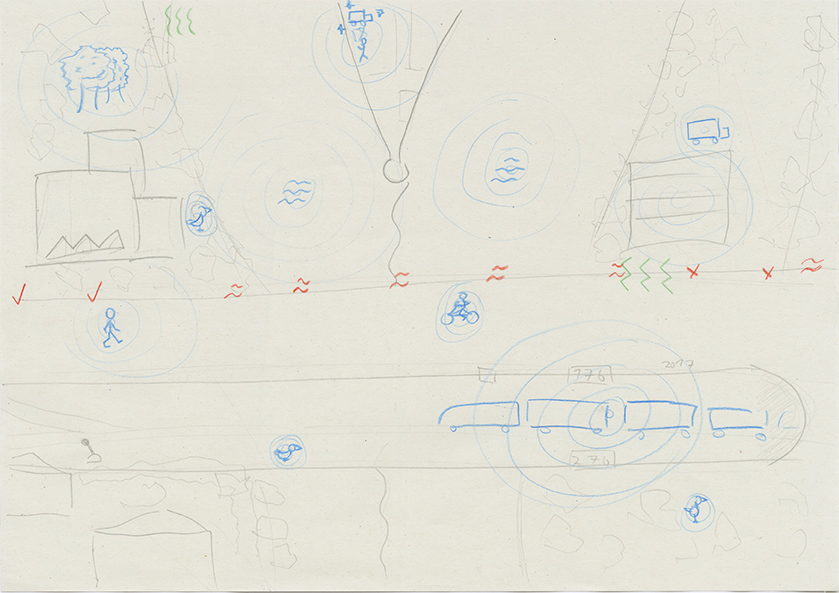

We carried out the exercise by walking back and forth along the Viaduc de la Jonction twice without any technology, taking only mental notes. Moving slowly, we tried to remain fully attentive to the surroundings. Afterwards, we went down toward the Rhône, near the cliffside, where a small rocky beach offered a place for focused listening. Calvo guided us to close our eyes and attend to the layers of sound—from the waves on the river to the incessant metallic pounding of machinery across from us. Afterwards, we went back to the classroom to produce our maps.

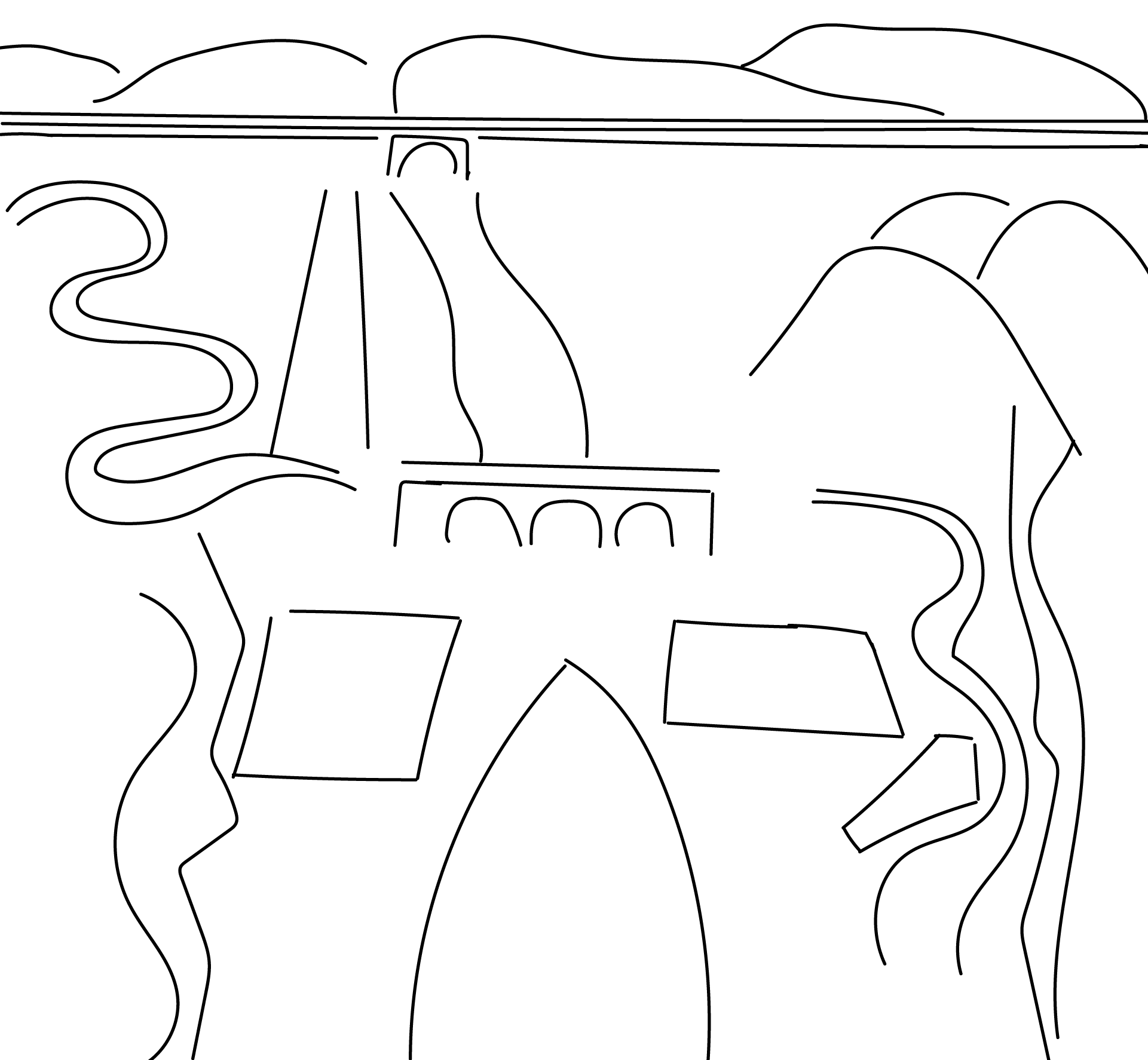

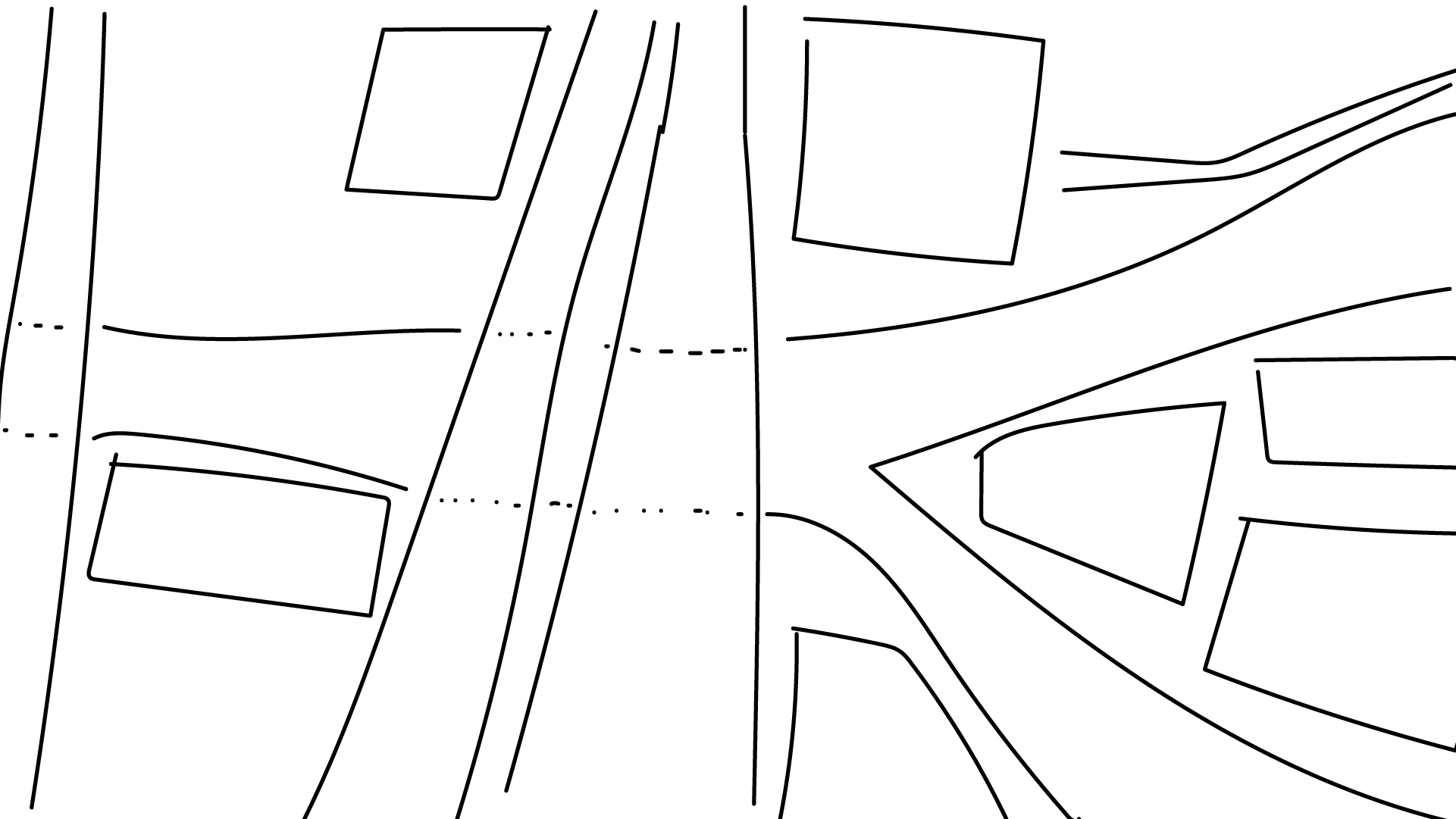

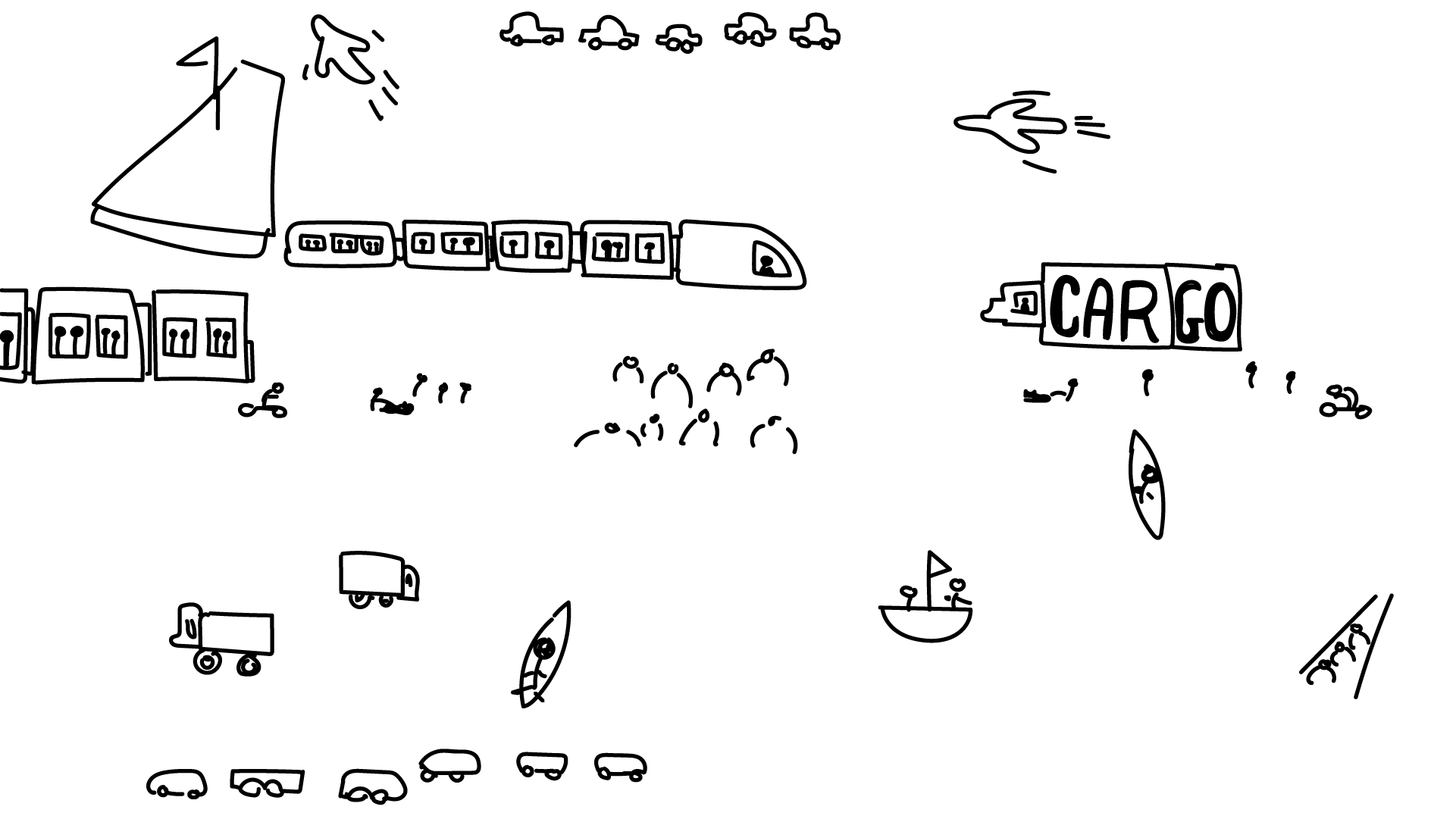

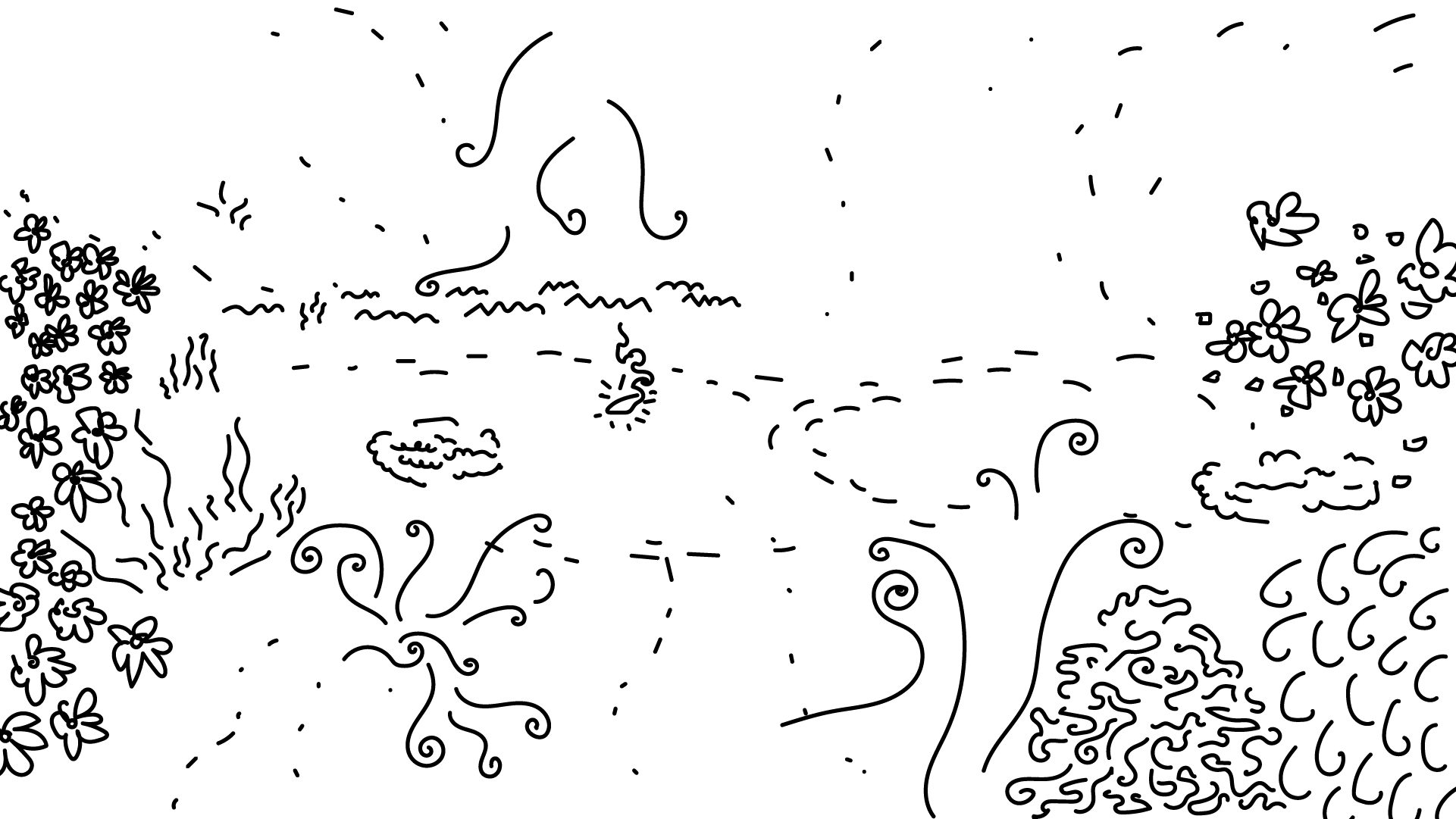

What I found remarkable in the maps produced by my peers was the diversity of perspectives. Not everyone had grown up in Geneva or had known the location. For some, it was their first encounter; for others, like Antonin Ricou[fig Illustration of Le Viaduc de la Jonction by Antonin Ricou and I, it was familiar terrain. Yet even as a regular visitor, I discovered new details—such as noticing cargo train instead of the passenger train I normally see. It was also nice to share a collective moment of seeing a swan swim downstream and then fly back upstream.

Illustration of Le Viaduc de la Jonction by Antonin Ricou and I, it was familiar terrain. Yet even as a regular visitor, I discovered new details—such as noticing cargo train instead of the passenger train I normally see. It was also nice to share a collective moment of seeing a swan swim downstream and then fly back upstream.

Since each person notices different things and brings a unique aesthetic sensibility, the resulting maps inevitably diverge.[fig Overlaying Maps by Chakir Ali. As Thomas Heyd, critiquing Carlson’s Natural Environmental Model, observes:

Overlaying Maps by Chakir Ali. As Thomas Heyd, critiquing Carlson’s Natural Environmental Model, observes:

[S]cientific knowledge may be neutral, or even harmful, to our aesthetic appreciation of nature, because it directs our attention to the theoretical level and the general case, diverting us from the personal level and particular case that we actually need to engage.75

If we had been instructed to focus on scientific or cartographic accuracy in order to produce a legible map, we might have missed the immersive, attentive experience the exercise was designed to foster. Interestingly, although Carlson is known for his cognitivist view, he also emphasizes the importance of bringing nature into the foreground through full sensory engagement. His model does not deny our sensual relationship to nature; rather, it argues that perceptual richness and scientific understanding can reinforce one another when directed appropriately. In this spirit, allowing each participant to approach the task in their own way fostered a more personal connection to the environment—and therefore a deeper appreciation—since we tend to remember what is experienced directly and personally more vividly than what is abstract or general.

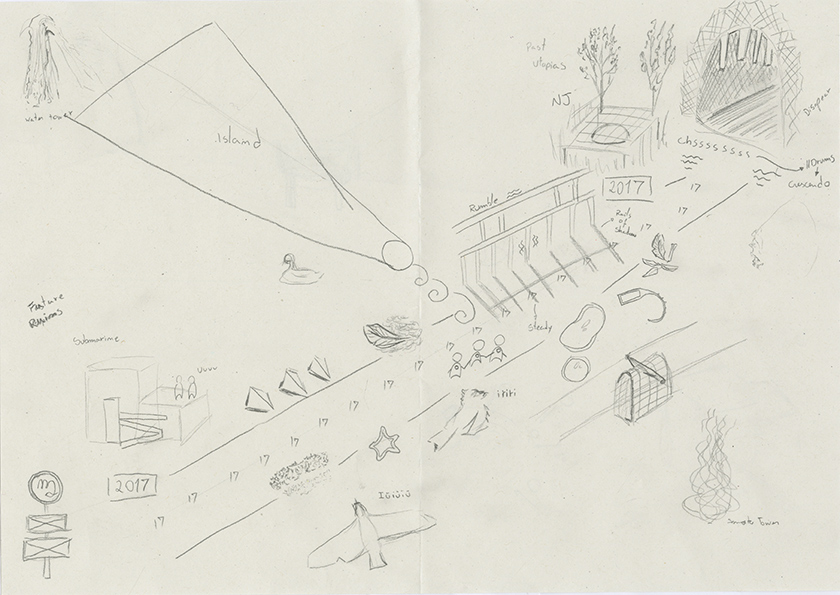

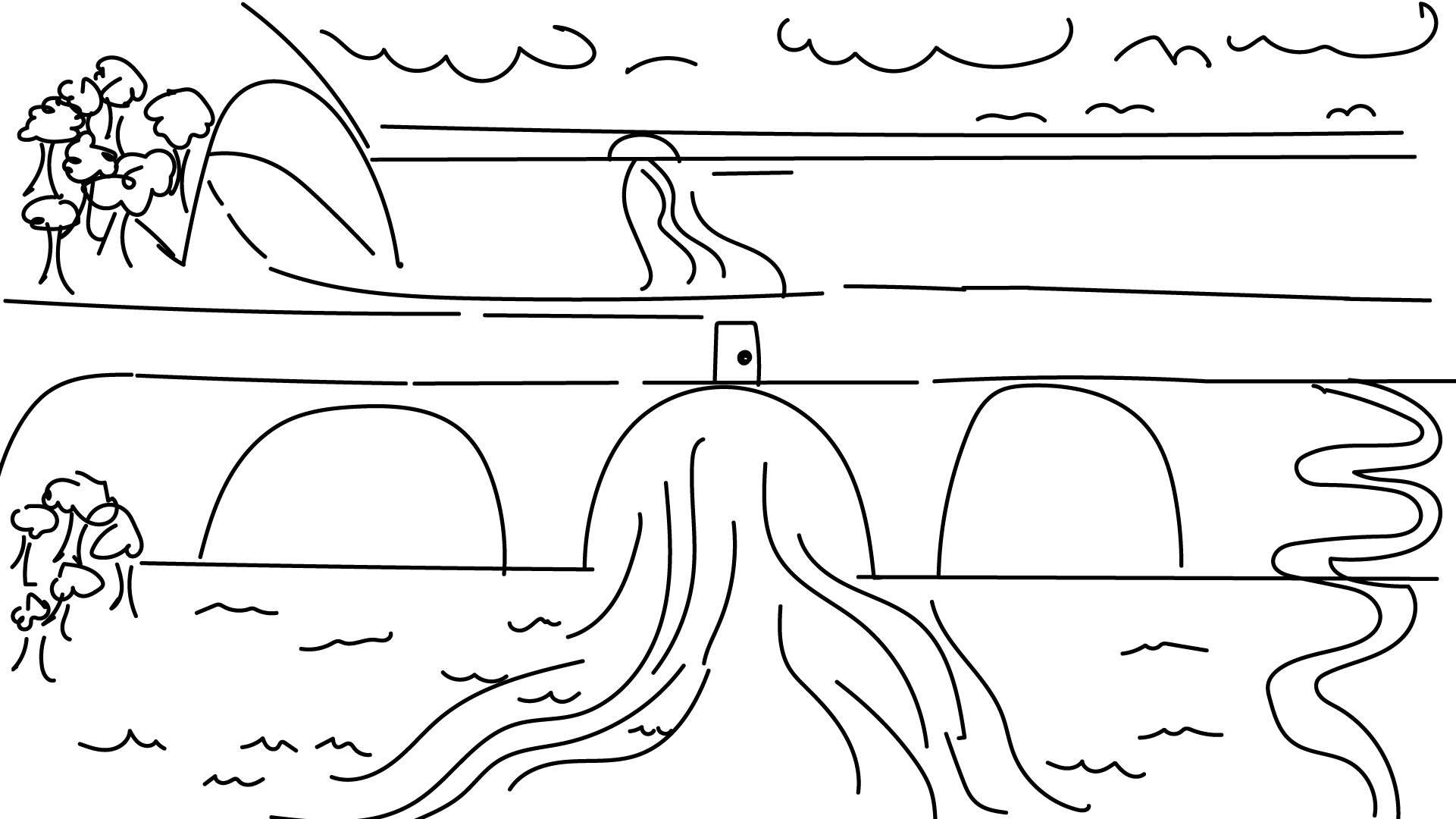

Similar from Ricou’s approach, I created a series of simple illustrations Line drawing of the confluence and the surrounding area by Peter Ha

Line drawing of the confluence and the surrounding area by Peter Ha Line drawing of the confluence by Peter Ha to reconstruct the location from multiple viewpoints and to draw on the cartographic language that reduces a place to lines. My aim was to identify and depict the landmarks that remained vivid in my memory—such as the viaduct, the rivers, the distant mountains, and the surrounding buildings.

Line drawing of the confluence by Peter Ha to reconstruct the location from multiple viewpoints and to draw on the cartographic language that reduces a place to lines. My aim was to identify and depict the landmarks that remained vivid in my memory—such as the viaduct, the rivers, the distant mountains, and the surrounding buildings.

From there, I created several maps based on different categories—landmarks[fig

Of course, going through the exercise and producing a visual output of my own was satisfying, but it also sharpened my observation skills and deepened my recollection of the location. Now, when I pass by each time, I find myself looking for new details rather than becoming hyper-focused on the confluence alone.

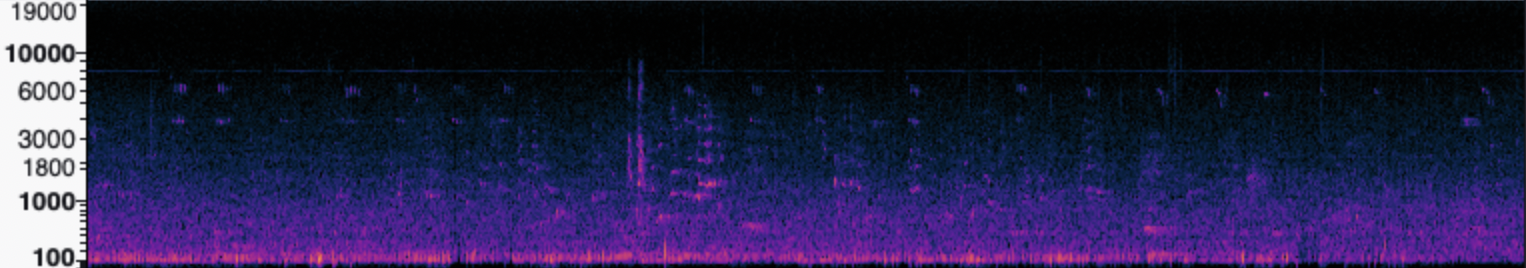

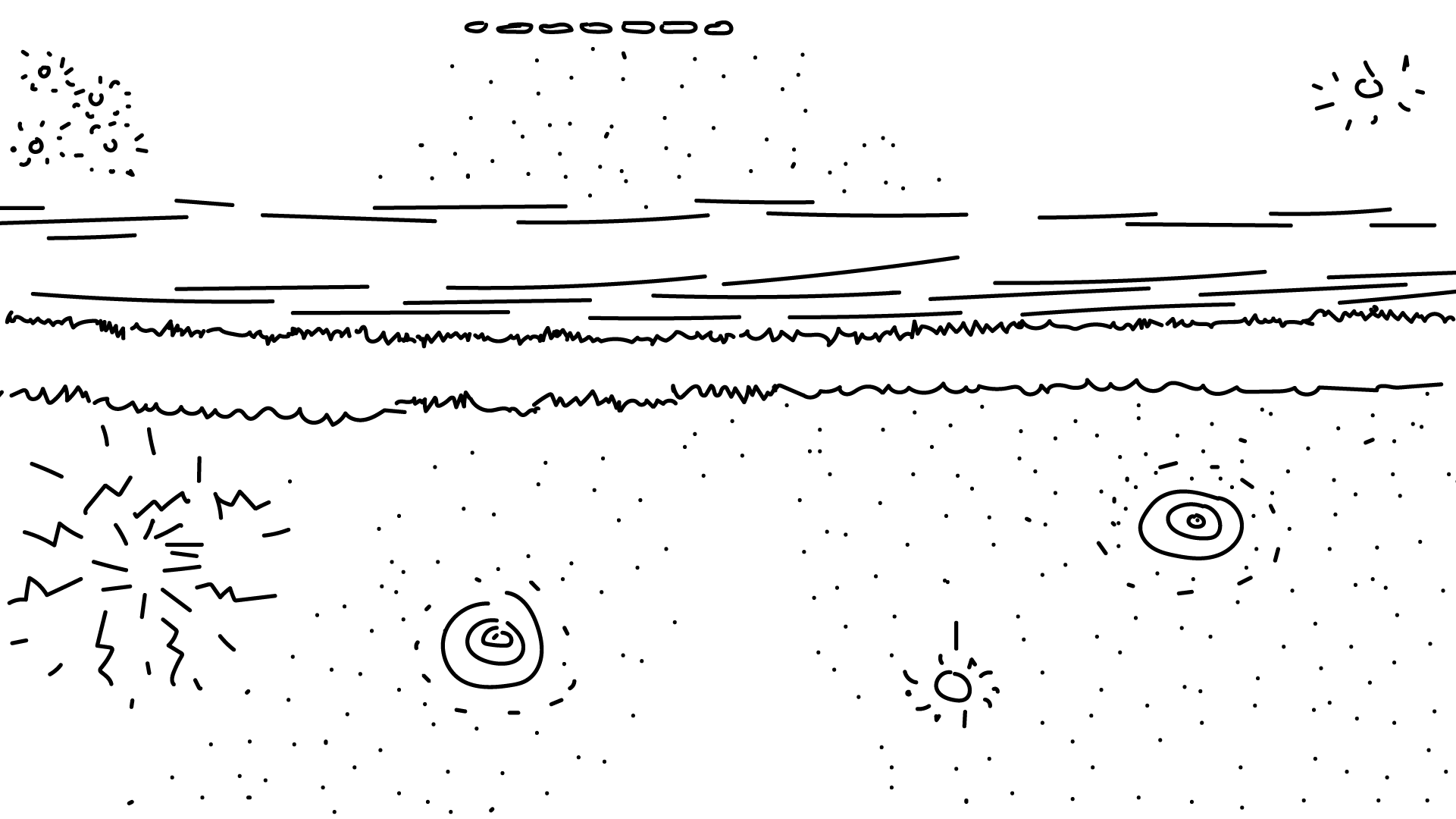

To extend the sound map and move beyond the purely visual, I also recorded the soundscapes of La Jonction at different times of day and uploaded the field recordings to Aporee, a platform that hosts environmental sound recordings from around the world. According to Bernie Krause, a pioneer of soundscape ecology, these sounds can be grouped into three categories: biophony, the sounds of living organisms such as birds or dogs; anthropophony, sounds produced by humans; and geophony, non-biological natural sounds like wind or waves hitting the bank.76 When I listened back to my recording Pointe de la Jonction 21.09.2025, I noticed a persistent high-pitched sound, which the spectrogram also made visible. Blips appeared at regular intervals around the 6000 Hz frequency, drawing attention to patterns in the soundscape that I had not immediately perceived on site.

Going through the process of putting on headphones, using a high-quality recorder, and editing the sound file in Audacity sharpened my attunement to sounds in the environment that I had not noticed before. When I later revisited the location, I was able to listen for this particular sound more intentionally, and I believe it may be a bird.

When I was uploading my recordings—particularly those made on the viaduct—I found myself instinctively labelling them as the “entrance” and “exit” of the bridge. This reflected my own routine: the south side marks the beginning of my day and feels like an entrance, while the north side feels like the exit. Yet, a bridge is fundamentally a passage, where entrance and exit are interchangeable, depending on one’s direction of travel. This personal bias shaped how I perceive the area, and it’s also evident in my line-drawing map Aerial line drawing of the viaduct by Peter Ha, where I rendered the south side larger because it is where my daily journey begins.

Aerial line drawing of the viaduct by Peter Ha, where I rendered the south side larger because it is where my daily journey begins.

After discovering Aporee, I wondered whether anyone else had created recordings around this area. This led me to an interview with Flavien Gillié, a Belgium-based sound artist and active Aporee contributor, who had also recorded the Arve. For Gillié, recording is not driven by a specific intention; he does it primarily for his own personal archive. During his visit to Geneva, making a recording was simply part of his habitual routine. He emphasized that he is more interested in the city than in “nature” in a traditional sense:

I wouldn’t say I’m a recorder of nature things. I’m not a naturalist. I live a lot in the cities and I make trips to cities mostly and I always like to record the interactions between people and everything else living somehow. So I try to find the liminal places, I mean going to the bank of rivers, you’re in the city but somehow you have to be a bit outside.77

Gillié raises an important point about rivers in urban environments—and about La Jonction in particular: rivers provide an escape from the city while remaining firmly embedded within it. One can never fully detach from the built environment, and this becomes obvious in the recordings themselves, where airplanes and trains crossing the viaduct are inseparable from the soundscape. The built environment has a measurable impact on the city’s ecology, and Gillié described how older recordings he made in Lyon once captured large flocks of starlings—sounds that residents say they no longer hear today. This growing quietness is echoed by acoustic ecologist Dr. Eddie Game, who notes that although we assume the world is becoming louder due to anthropogenic noise, it is in fact getting quieter because fewer species are vocalizing.78

In addition, there is the broader issue of nature receding under anthropogenic noise. In a YouTube video by Swiss musician, DJ, and artist Jonas Fasching, I noticed that he repeatedly had to pause his field recordings because planes kept passing overhead.79 When I later visited him in his studio in Bern, he mentioned a similar challenge underwater: even beneath the surface, the sounds of boats intrude. I was curious to hear how he navigates these disturbances from a more naturalist perspective, and how such conditions shape the way he approaches field recording:

I really enjoy all sounds. I also enjoy recording in the city, and I enjoy recording when there are people around, or some languages that I don’t understand, or just things that people do. So for me, it’s not always a distraction. But of course, when you want to record the pure nature sound, it can be really annoying. Especially in Switzerland, there’s almost no time where there’s no plane in the air. And you really start to realize it when you start to record. Because it’s super hard to find a moment where you have five minutes of nothing. It’s almost impossible in Switzerland. But I think as an artist using these sounds you just have to get creative with what you get and it’s fine in a way. But it really makes you very much aware of how much sounds there are by humans caused by humans. And also how humans change the sounds in the environment.80

So not only have we altered landscapes—and with them the ecologies in which many species once thrived—but we have also overlaid these environments with our own noise, adding further disturbance. If this is the case, the question becomes: how might we bring nature back into the foreground by giving back its voice?

Giving Voice to Rivers

Bringing nature forward by letting its own agency come into view

Personhood

There is a growing movement in favour of granting rights to rivers around the world. One of the earliest successful cases invoking the Rights of Nature was the 2011 Vilcabamba River decision in Ecuador. Under Ecuador’s 2008 constitution—which recognizes the Rights of Nature—the court ruled that the river had the right to exist and to be protected.81 As a result, people were legally allowed to petition on the river’s behalf whenever its rights were violated.

In addition to constitutional Rights of Nature, some rivers have also been granted legal personhood, such as the Whanganui River in New Zealand and the Magpie River/Muteshekau Shipu in Canada.82 The distinction is that a river, as a legal person, is regarded as an entity that holds subjective rights—legal entitlements assigned to a specific rights-holder.83 But these rights should not be confused with subjective experience; they do not answer the question of “what it is like to be a river, ” a perspective that remains inaccessible to us. As Thomas Nagel argues in “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?”, we can never fully grasp the inner experience of another being; our understanding is always filtered through our own senses, assumptions, and point of view.84

As Anila Srivastava explains, “Legal personhood…connotes legal autonomy, that is, the ability to act, rather than be acted upon, within the legal system.”85 In this sense, legal personhood gives a river an active “legal voice, ” enabling it to advocate for its interests through appointed guardians. In many cases, these guardianship structures are jointly defined by Indigenous communities and government bodies.

A major force behind these movements is Indigenous communities whose ancestral and cultural relationships to the land shape their legal and political demands. In Is a River Alive?, Robert Macfarlane travels to my home country, Canada, to meet with the Innu people involved in the effort to grant legal rights to the Muteshekau Shipu. He cites the words of Lydia Mestokosho-Paradis:

It seems crazy that we give a corporation that’s ten years old rights, but we won’t give rights to a ten-thousand-year-old river. Water is life. Water is the medicinal plants. Water is the berries, the fish, and all the other animals that drink the water. If you don’t have water, everything else dies around it. The river is life—it’s like when you see a place, but the colours there are not bright. But when we see the river, when we’re near the water, the colour is…popping! You know—that’s how we feel. When we go to the river, I feel more alive. I see the people more brightly. The land is healthier.86

As Mestokosho-Paradis notes, we rarely question the legal status of corporations87—a point that Jens Kersten, a Public Law and Governance professor in Germany, also agrees that:

The recognition of nonhuman actors as legal persons with subjective rights is nothing peculiar. We do it all the time in the economic sphere. Over centuries, we have gotten accustomed to the idea that firms or trusts are legal persons with rights and obligations. Nobody questions this.88

While legal scholars and Indigenous communities work together to shape the future of environmental law elsewhere, what does this look like in places where there are no Indigenous communities acting as custodians of the land? In such a context, who is able to speak on behalf of the rivers? In the case of the Rhône, the advocacy came from id-eau, an association based in Lausanne, Switzerland. The group was created to bring people together and to encourage public participation in protecting water as an essential and vital resource.89

In 2021, id-eau launched an experiment called the Assemblée Populaire du Rhône, in which 25 residents from across the Rhône watershed in Switzerland and France met over two years. The process consisted of six sessions, each lasting three days. The goal was to identify key issues affecting the river and to imagine forms of collective governance. Among the main takeaways were the importance of long-term thinking, prioritizing biodiversity, and recognizing the river’s inherent value beyond its economic utility to industry.90 In addition to this initiative, id-eau also launched a petition to grant legal personhood to the Rhône. However, the effort was unsuccessful, and the association is no longer pursuing this endeavour.91

Prosopopoeia

Advocacy is one way of giving voice to rivers, but artistic and design practices offer another—through the device of prosopopoeia. While personification merely attributes human form or qualities to nonhuman entities, prosopopoeia goes further: it grants them the capacity to speak or act within a narrative. In this sense, it parallels legal personhood, which similarly enables a nonhuman entity to take action and be represented, rather than simply being described or adorned with human traits. Pierre Fontanier offers a useful distinction between the two concepts. He writes:

Prosopopeia, that must not be confused with personification, apostrophe or dialogism, which however do almost always occur with it, consists in staging, as it were, absent, dead, supernatural or even inanimate beings. These are made to act, speak, answer as is our wont. At the very least these beings can be made into confidants, witnesses, accusers, avengers, judges, etc.92

What I find compelling in Fontanier’s definition is that prosopopoeia is fundamentally about activity—about enabling an entity to act, speak, or intervene. This aligns with Carlson’s call to bring nature back to the foreground, as it shifts our stance from passive appreciation to a more active, participatory form of engagement. Crucially, prosopopoeia does not depend on projecting human qualities onto the nonhuman; rather, it grants a “voice” to the voiceless, allowing nonhuman beings to appear as agents in their own right.

If prosopopoeia grants the voiceless a mode of appearing, then certain sound artists enact this almost literally. I spoke with Ludwig Berger—a French sound artist, researcher, and educator whose work explores the sonic qualities of species and landscapes—about his practice and one of his ongoing projects. His long-term project Crying Glacier began at ETH Zurich as an assignment with his students and has since developed into a decade-long engagement with the Morteratsch Glacier in the Swiss Alps, the very source of the Ova da Morteratsch river. Using hydrophones and geophones, he records the acoustic activity of this non-biological entity, capturing vibrations and resonances that would otherwise remain inaudible. For Berger, the project functions both as environmental advocacy and as an archive: a way of preserving the glacier’s voice in a moment when its future is uncertain.

While Berger’s recordings do not obviously contain human speech, we inevitably interpret them through a human perspective. Yet for Berger, this limitation does not stop him from forming a relationship with the glacier. He approaches the glacier not as a mere location, but almost as a person—an entity he returns to, listens to, and forms a connection with over time. When I asked him to describe the glacier’s personality, he responded:

Yeah, I think it has many different personalities in a way, as it has, like many different voices, that I can hear. So, I have a lot of respect from this personality. I mean, it’s obviously very large. It has a very large scale, and so it’s intimidating in some ways. And I mean, just the sheer scale of it is very intimidating, but also the sounds that you can hear. I mean, when I’m standing on it, and sometimes they’re like these super deep [sounds], you know, and then you realize you’re really standing on something that is moving, and you’re like this small [being], and you could just like fall down a crevice or whatever.

So, there’s this whole thing of like fear and respect that I have to towards this glacier person, if you will. But yeah, there are also like in these little air bubble sounds. They’re all so funny and quirky, and yeah, they make me laugh sometimes, you know. And there’s a tenderness even to these very delicate ice sounds. And it also has something lamenting. Yeah, so it’s really a mix of this. How do you say fearsome, like, fear inducing, and funny and sad, and many, many things at the same time.93

It is clear that, for Berger, the glacier is not merely a mass of slowly shifting ice but an animate presence in its own right. His project has since attracted public interest from journalists and even government bodies such as the Green Party of Switzerland. This response demonstrates the power of making the invisible perceptible: by conducting field recordings and presenting them through documentaries, installations and playlists, Berger enables the glacier to appear—to be heard—in ways that resonate beyond the scientific domain. Whether any of this will actually slow the retreat of the glaciers remains debatable, since climate change cannot be mitigated through awareness alone—although awareness is a step in the right direction. Instead, the project functions as an archive of what may soon be lost, a reminder that these vast, seemingly immovable and often forgotten formations possess a kind of ‘life’ of their own.

Proxy A.I. Poet

Up until now, I have sidestepped the obvious question, but for a media design thesis, it feels necessary to address it: how does artificial intelligence shape, mediate, or influence our appreciation of nature? Two projects illustrate this emerging inquiry: Matteo Loglio’s Natural Networks (2017) and Superflux’s Nobody Told Me Rivers Dream (2025). In both cases, river data serves as input to an AI system that expresses itself in a poetic tone.

Loglio’s project centres on London’s canals, where he collected environmental data using floating buoys that transmitted their readings over the internet to a neural network. This data was then processed by a machine-learning model trained on 20th-century poetry, enabling the system to generate poetic responses shaped by the conditions of the waterways.94 An excerpt from the resulting text reads:

The hazy river full of leaves,

churned the Somerset Coal Canal.

The icy travelers washing their

Necks and disappearing into

The morning walk…95

The project was exhibited at the London Design Festival, featuring several outputs, one of which was a video installation in which the generated poetry appeared alongside the data that shaped it—weather readings, time of day, and geographic coordinates. Rather than presenting raw data directly, Loglio translates these shifting conditions into a more accessible and affective form. The aim is to foreground the dynamic qualities of the canals and to encourage the audience to imagine the waterway as something more than infrastructure—perhaps even as a voice in its own right. Viewers are prompted to ask what the London canals might sound like if they could speak, and whether the poetic register Loglio uses aligns with their own sense of the river’s character. This act of questioning invites reconsideration of one’s relationship to the canals and, more broadly, helps bring the city’s natural elements back into awareness.

Superflux’s project Nobody Told Me Rivers Can Dream was exhibited at the Design Museum as part of More than Human: Making with the Living World. For this work, the studio designed three sensor-sculptures positioned along the landscape of the River Thames, each dedicated to capturing a different aspect of the river’s ecology: one records birdsong, another measures water flow, and a third monitors weather conditions. Each sculpture is fitted with an LED display that transforms the collected data into short poetic prompts for passersby, generated through an AI system. Superflux describes their use of AI in the project as follows: